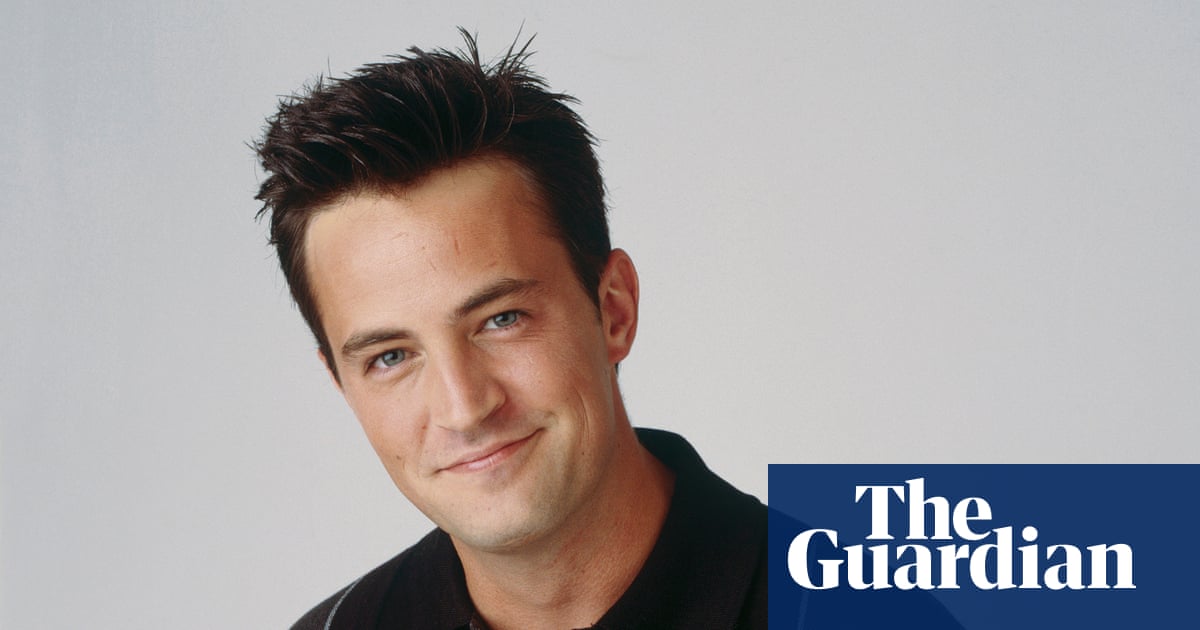

Watch the third season of Friends, writes Matthew Perry in his memoir, and you can see how thin he had become by the end of it. “Opioids fuck with your appetite, plus they make you vomit constantly,” he writes. Look again, and yes – his fragile wrists emerge from a shirt that looks as if he has borrowed it from someone far larger, his trousers hang off him – and it’s unbearably sad now, with the knowledge that addiction would kill Perry nearly 30 years later, at the age of 54. At the time, most people watching probably wouldn’t have noticed, dazzled instead by Perry’s sharpness and immaculate comic timing as Chandler Bing, the show’s dry wit. He was having to take 55 Vicodin pills a day – an opioid – just to function and avoid terrible withdrawal symptoms, but he was never high while he was working, he writes in Friends, Lovers and the Big Terrible Thing, which came out in 2022. He just had to make it to the end of the season so he could get help. Had the series lasted for more than its 25 episodes, he thought it would have killed him.

That was the first time Perry went into rehab. He was 26, and one of the biggest stars in the world. There would be more than 65 attempts to detox from drug and alcohol addiction over the next decades until his death in 2023. Last week, a doctor was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison for supplying ketamine in the lead-up to Perry’s death (though not the ketamine that killed him); three others who have pleaded guilty will be sentenced in the coming months.

Perry’s manager, Doug Chapin, and publicist Lisa Kasteler-Calio had been working with Perry for more than 30 years. After he died, they launched the Matthew Perry Foundation, to support addiction treatment and recovery, and campaign to reduce stigma. Perry had long talked about the idea of an organisation doing both. By October 2023, Kasteler-Calio, one of Hollywood’s powerhouse publicists, had already decided to step away from the agency she had co-founded. She texted Perry – he was a big texter, she says – to see when he was free so she could go over and tell him in person. He immediately called her. “I was going to continue to work with him on [the foundation] and a few other ideas that he wanted me to be involved in,” she says, when we speak over Zoom, joined by Chapin.

That was three days before he died. “The tragedy on top of the tragedy of losing Matthew is that he was ready to do the work,” she says. Chapin says: “Here we were, stopped mid-sentence, so there was nothing except, well, I guess we have to complete this. That was the driving force.” Kasteler-Calio points out that Perry had always said he didn’t want to be remembered for Friends, but as someone who had helped others. “We didn’t have to search for the mission. We had it. He wanted to help as many people as he could, it’s that simple,” she says.

Chapin became Perry’s manager in 1992, and introduced Perry to Kasteler-Calio just before it became clear that Friends – which launched in 1994 – would become huge. He was “adorable”, remembers Kasteler-Calio. “I think the reason people fell in love with Chandler is because the real Matthew came through.” Chapin remembers Perry as a young man who didn’t really change over all the decades they knew each other, when he was “what he always was – lovely, smart, funny.”

Chapin is clear that while Perry craved fame, his struggles pre-dated the pressures it brought (Perry had his first drink at 14). “The pressures and the demons are not unusual for people who are very talented. I don’t want to make a mass determination, but it’s a particular kind of person that looks to have everybody know them and to be famous.” But fame and attention, he says, “amplify the pressure to some degree. More importantly, it made it very hard to have his problems happen in private.”

It also killed Perry’s fantasy that if only he could become famous, he would feel better about himself. “He found himself with the number one TV show and the number one movie [The Whole Nine Yards], and, boom, his other struggles still existed,” he says. That wasn’t specific to Perry, he adds. “What was specific to Matthew is crazy loyalty,” says Chapin, adding that that is vanishingly rare in Hollywood. “There’s a reason we worked with him for 30 years. He kept his group of friends close. He kept his representatives close. He inspired loyalty, but he also gave loyalty, that was just one of his characteristics.”

Neither had any idea that Perry was struggling at the beginning. “He was working so much, he was doing the show and doing a movie in the breaks, there was such intensity of work that I think it masked some of it,” says Chapin. He adds that also, Perry’s addiction “was not as much of a challenge [then] as it became for him.” Kasteler-Calio says: “Matthew felt a deep sense of responsibility to the other five [on Friends]. He showed up every day and he did the work. He wasn’t somebody who was out in the clubs and all of that.” He was drinking at home, and taking drugs. “Because this disease is so isolating, he was not publicly, like a lot of others, displaying his disease.”

By the seventh season in 2000 – he had signed the deal in hospital, while being treated for pancreatitis caused by excessive alcohol – Perry’s castmates were sufficiently worried to take him aside and tell him they knew he had a problem. Chapin and Kasteler-Calio say that Perry was always very open with them. “There was never the situation like, ‘Oh, we know something’s happening, but we can’t talk to him about it,’” says Chapin. “He’d be the person, when it got bad, who would say, ‘I need to stop and get help.’ I don’t want [people] to have the picture that Matthew was, for lack of a better word, a victim of the disease, because he was engaged in trying to recover, always.”

But it must have been difficult at times for them to do their jobs, and keep Perry’s career going for him. And there were times, admits Chapin, “where the disease collided with the work. I think it’s better that those stories come from [Perry’s] book than from us.” Neither want to dwell on episodes where productions were postponed because Perry wasn’t well – the 2002 film Serving Sara, or some of his scenes in Friends – or the times he did show up, such as on the CBS show The Odd Couple, but was unreliable. If Perry’s addiction did make their jobs tricky at times – and it must have done – there was no question that the priority was always his health. Kasteler-Calio, still protective, points out that when Perry did have to remove himself from work, on his return to sets he would go around “and apologise to each and every single person”. Many big name actors would not have done that, she adds.

Although it became the story, Perry’s addiction is far from the whole picture. There were also stretches of sobriety, one of which brought him an Emmy nomination for his role on Friends, and there was the play he wrote and opened in London, the dark comedy The End of Longing, the TV shows he wrote such as the ABC sitcom Mr Sunshine, which he also starred in. “I miss the creative side of him,” says Chapin. “He was very smart, creatively, and that’s very energising to be around.” Kasteler-Calio misses the way he made her laugh. “There are just many things, as life happened, that Matthew was a part of. I remember all of that, because that’s where his kindness and the compassion came through.”

When he was struggling, she says, he didn’t hide it. “He wasn’t a difficult person. I’ve had plenty of difficult clients. I didn’t have a difficult day with him.” He was not, adds Chapin, “a temperamental guy. He was a lovely, sweet person who had a personal struggle and was always fighting to be the creative, engaged person he loved being, and trying not to succumb to this other thing, this disease.”

For Kasteler-Calio, the bigger challenges came from dealing with a media intent on getting stories about Perry – his struggles were excessively documented – not from the actor himself. In her five-decade PR career, the celebrity clients “that were the most challenging when they got into crisis are the ones that didn’t want to listen, that thought they had all the answers. That was not Matthew.”

There were a couple of pivotal positive moments in Perry’s experience of addiction and attempts to get better. One was the therapist who told him it wasn’t his fault, that it was a disease. “Coming to the understanding that he was battling with a chronic illness changed his whole mindset around it,” says Chapin. The other was the publication of his 2022 memoir – funny, self-deprecating and brutal. “He was always, throughout even his worst times, very helpful and engaged with other people,” says Chapin. “They would come to him because he had so much experience with the disease [and treatment] that he knew a million avenues to suggest.”

The book was a way to reach people on a massive scale. “It was the big removing of the Band-Aid of shame, for him,” says Chapin. “It was a very important step for him. We come back to the stigma and he was always very conscious that the guilt and the shame around [addiction] was part of the struggle. The book was his way of going, ‘Here I am, everything about me, good, bad and ugly.’ Presenting that out into the world and getting all the love back that he got for it was transformational for him.”

They had always told him how loved he was, says Kasteler-Calio, but Perry would shrug it off. Now, she says, with audiences coming to hear him speak or the people who wrote to him of their own struggles, “it was right in front of him. You couldn’t deny the impact, and it was Matthew having the impact, not Chandler. As hard as the struggle was for him, conversely, being able to help people was equal to that. That’s why, once we lost him, there was no question that we needed to create this foundation and do this work.”

Tackling stigma is one of its fundamental missions. Only 50% of Americans, says Kasteler-Calio, “recognise that [addiction is] a disease. The rest feel like it’s a moral failing, and that you should just get over it, and that’s not right.” This includes some of the medical profession, she says. “Doctors are not trained in how to treat this disease.” It should be required training for all, not just for specialists, so that any doctor can recognise it, signpost people to the correct treatment – and be careful with their prescribing.

Perry writes that had he not taken the painkiller one doctor gave him on a film set early in his career, after he had injured himself in a jetski accident, perhaps “none of the next three decades would have gone the way they did”. Coming out of a two-week coma in 2018 – the result of a burst colon, followed by pneumonia, caused by the stresses his body had been through – he was put back on opioids. The foundation works with Dr Sarah Wakeman, an expert in addiction medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and they have established a fellowship in Perry’s name to help train doctors. “One of the things that is important when we’re talking about this is that recovery is possible, this is a treatable disease,” says Chapin. “The more skilled we get at treating it, the more we’re going to see examples of recovery.”

A summit held by the foundation in September brought about 200 experts together, along with people and communities with experience of addiction, to build partnerships and share knowledge about everything from treatment to policy. A week later, the foundation was speaking at the Clinton Global Initiative, run by Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton, about the impact of stigma, and how to end it. At the less high-profile end, one of the first things the foundation did was to give money to about 20 grassroots organisations they had identified across California which were helping people with addiction and desperately needed funding. Kasteler-Calio smiles when she said she spent two days on Zoom calls, offering the money and trying to convince people it wasn’t a scam. “What people have to go through to apply for grants, it’s expensive, it takes a lot of time. We wanted them to have access to the money immediately,” she says.

There are employment initiatives to support people in recovery with getting back into work, and the foundation supports Bridge, a project led by doctors that aims to provide joined-up treatment for people with addiction who are leaving prison. “Because of our experience with Matthew, [we know that] it’s a multi-pronged disease, and you’ve got to hit it from a whole bunch of different directions at once,” says Chapin. “There is a medical aspect, the psychological aspect. There is also a community aspect to it. People don’t heal from this alone in a room. What we experienced throughout the Matthew experience was that there are all these holes in the process of recovery.” For many trying to recover, “You can get six weeks of sobriety in a shelter, and then there’s nothing, you’re on the street. There needs to be a wholeness, because the process needs to be sustained for a really long time. What we are looking at is where are the holes that we can fill?”

Perry, say both, is present in all of this. “The six months of crying, that happened already,” says Chapin. “The rest has been working on his project, so he’s still right here with us, every day.” As for his ongoing grief, this is, he says, “the treatment”. Kasteler-Calio smiles and says, “We’re doing what Matthew wanted. He said it over and over: I want to help as many people as possible. Of course, we wish we were doing this with him. I miss him like crazy, but the best thing that we can do is just keep doing this work.”

#hidden #life #Matthew #Perry #stop #Matthew #Perry