Once a month, American labor activist Jim Keady logs into Remitly, an app for transferring money abroad, at his New Jersey home and sends $100 to a former Nike factory worker in Indonesia.

Cicih Sukaesih helped bring the world’s attention to the lives of the young women in poor countries who made sneakers in the 1990s, first by organizing a strike and later by marching onto Nike’s bucolic corporate campus in Oregon to demand a meeting with co-founder Phil Knight.

Her story — at a time of police and military harassment of labor organizers abroad — caught the attention of The New York Times and other news organizations. It also helped inform a generation of workers about their rights.

“She helped to birth, I would argue, the Indonesian trade union movement within Nike’s supplier factories,” Keady said.

But media attention and accolades don’t pay the bills. Cicih had trouble finding work following her 1990s activism. (Cicih prefers to go by one name. It’s pronounced “Chee Chee.”)

Decades after her crusade faded from the headlines, Keady and other labor organizers began sending Cicih money to keep her afloat.

“She took a stand and she was a revolutionary,” Keady said. “And she has nothing to show for it.”

Now 62, Cicih welcomed a reporter for The Oregonian/OregonLive into her home last year, part of a reporting trip that included interviews with about 100 workers who make Nike sneakers, mostly in Indonesia, which was ground zero for the decade of sweatshop criticism that stained Nike’s reputation in the 1990s.

Cicih said she’s proud of the example she set by standing up to Nike. She said workers “became aware of their rights and aware of the law.”

“Many things changed,” she said.

The advocacy led to improvements, she said, including cracking down on child labor, installing better safety equipment and providing menstrual leave.

“Many of my friends,” Cicih said, “became brave enough to speak up.”

But she described her work as incomplete because problems linger, including chronically low wages.

Nike did not address specific questions about Cicih’s experience or about the Nike supplier that employed her in the 1990s, nor did Knight provide comment. Instead, Nike issued a broad statement saying, in part, “We’re appreciative of the efforts that individuals and organizations, including Cicih, have made in helping push the industry forward.”

Nike said the company has been “deeply committed to advancing a responsible and resilient supply chain for more than 30 years” and that while progress hasn’t been perfect, it has sought “systemic improvements across the industry.” Nike’s goal, the statement said, is that “all people involved in the manufacturing of Nike’s products are respected, valued, and treated fairly.”

Cicih keeps tokens of her activism in her home, including a framed poster that depicts a factory worker and reads, “Who made your shoes?”

Jeff Ballinger, a labor organizer who was prominent in the 1990s’ anti-sweatshop movement, gave it to her. In an interview, Ballinger said he still considers Cicih a “hero” — albeit unsung, even in Tangerang, the industrial hub where the Indonesian factory movement took off.

“Like in wartime, some people just step up,” Ballinger said. “In a perfect world, there’d be a statue of her in Tangerang.”

$1.26 a Day

Cicih sat for an interview in a backyard filled by a chicken coop and a small garden that included pumpkins, bananas and edible bamboo. The small house she and one of her sisters inherited from their parents in Menes, her childhood village about a 90-mile drive west of Jakarta, is now home.

After putting out snacks that included a traditional Indonesian dessert made from rice and grated coconut in banana leaves, Cicih often flashed a wide grin as she reflected on a life intertwined with Nike’s emergence in her country.

Nike, then known as Blue Ribbon Sports, bought its first sneakers from Japanese factories in the 1960s. But as Japan’s wages rose, it shifted manufacturing to lower-cost Asian countries, including Taiwan and South Korea.

In 1988, it started making sneakers in Indonesia.

The country had a terrible human rights record, but it was eager to attract foreign investors. Factories in Jakarta paid wages as low as $1 a day, compared with $8 in South Korea, $14 in Taiwan and $33 in Tokyo, according to a 1988 State Department report.

In 1989, five years after she graduated from high school, Cicih joined one of her sisters making Nike sneakers at the Sung Hwa Dunia factory 40 miles west of Jakarta, Indonesia’s biggest city.

She started work each day at 7 a.m.

At first, she said, she cleaned glue and chemicals off sneakers with her bare hands. Then she moved to a glue line, attaching soles to shoes. The factory was poorly ventilated. Co-workers coughed from the fumes. Cicih recalled seeing one person faint and then return to the assembly line because factory managers didn’t give her permission to go home.

(The factory is still open, but it has changed owners and now has a different name. The current owner did not respond to emails. The previous owner could not be reached.)

Worker safety was “very, very bad,” Cicih said through an independent journalist The Oregonian/OregonLive hired to translate the conversation.

“There were many, many labor laws that the company did not follow,” she added.

Like today, the vast majority of factory workers were young women. Most of the managers were older men, which Cicih said led to a natural power imbalance and problems with sexual harassment.

“I have watched and seen a lot of women being sexually abused, or touched inappropriately,” she said.

There was constant pressure to meet daily production quotas.

Cicih made $1.26 a day, around minimum wage. A 1989 study found the minimum wage was so low that many factory workers were malnourished.

“It was not enough for me to get by on a daily basis,” she said. “However, I had to make it on the amount I received.”

Cicih often worked overtime until 9 p.m. Sometimes she worked on Saturday and Sunday, which she considered forced labor. The amount of overtime, she said, motivated her to “rebel.”

“A Wage Increase Was the Top Priority”

The turning point for Cicih came when one of the company’s buses, which workers rode to the factory and were always overcrowded, flipped and killed a co-worker.

“How can we protest this issue to the company?” she asked another co-worker.

Unbeknownst to Cicih, this co-worker had joined an organization that taught workers about labor rights. Cicih faked a doctor’s letter, got a sick day and took a class.

Through the organization, she met Ballinger, who had moved to Indonesia to organize factory workers. In 1992, Ballinger wrote a story for Harper’s Magazine that compared the wages of Sadisah, one of Cicih’s co-workers, to the earnings of Nike endorser Michael Jordan. Sadisah earned 14 cents an hour. It would have taken her more than 44,000 years to make what Jordan earned from Nike in a single year.

Cicih started skipping lunch and prayer breaks to organize her co-workers.

On Sept. 28, 1992, Cicih and workers from her factory went on strike. The New York Times reported 600 walked out, but Cicih and other activists have put the number of strikers in the thousands. They demanded better treatment of women, better union representation, better food, better transportation and, most importantly, better pay.

“A wage increase was the top priority,” she said, holding up the original document that listed protesters’ demands.

Her activism came with great risks. Around that time, Marsinah, a factory worker who was recognized last year as the country’s first National Hero from the labor movement, was kidnapped, tortured and murdered.

“Military and police were everywhere,” Cicih said, but she said her desire to help her co-workers “eclipsed all the fear.”

The strike lasted two days.

It ended after the factory agreed to increase wages for many employees, Cicih said, but she added that her seniority made her eligible for just a small raise. The company accepted other demands, including allowing menstrual leave. Cicih said she was the first worker to take it.

That same year that Cicih led the strike, Nike released a code of conduct, becoming one of the first brands to do so. Codes of conduct have since become the default method companies like Nike use to police overseas factories. The basic system: The company writes rules and contract factories agree to follow them. Auditors monitor compliance.

A few months after the strike, Cicih and roughly two dozen of her co-workers got laid off. Leslie Milano, a prominent American labor organizer in the early 2000s, said unemployment at the time was high in Indonesia.

“That’s why a lot of people didn’t want to do what Cicih did,” Milano said. “They didn’t want to lose their jobs.”

Cicih said that not long after being laid off, she was hauled into a police station and spent two days being pressured to confess to destruction of property and causing a disturbance. She was not allowed to go to the bathroom, she said.

Cicih said the police made her watch them beat a suspect. Then they made her sit in his blood, she said, before releasing her.

The Indonesian embassy in Washington, D.C., did not respond to questions about military repression of worker rights in the 1990s. (The country undertook democratic reform after the dictator Suharto stepped down in 1998, although problems remain.)

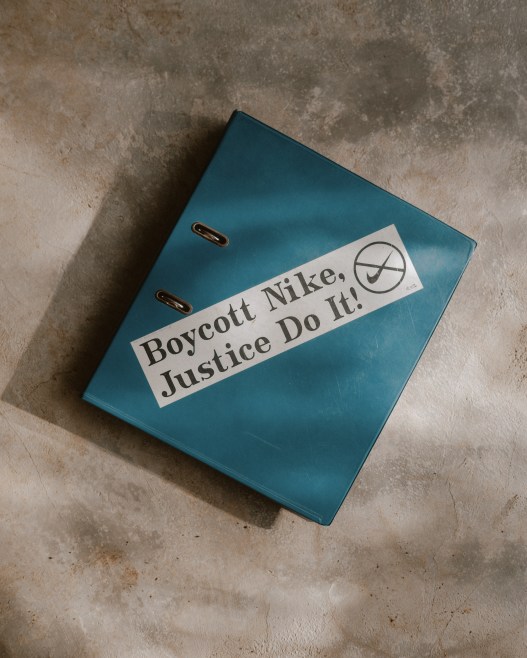

After her release, encouraged by Ballinger and others, she joined co-workers in filing a lawsuit against the factory alleging wrongful termination. The lawsuit went all the way to Indonesia’s Supreme Court. In 1996, Cicih and her co-workers prevailed. She got about $200 in back wages. She still has the check in a binder with other documents from her organizing days.

For two years of lost wages, Ballinger figures Cicih should have gotten more than $2,000. That would have been enough to set up a small business.

“It would have been a hell of a lot of money back then,” he said. The movement’s failure to deliver greater restitution to Cicih and others “is something that I’ll never get over.”

Cicih Comes to Oregon

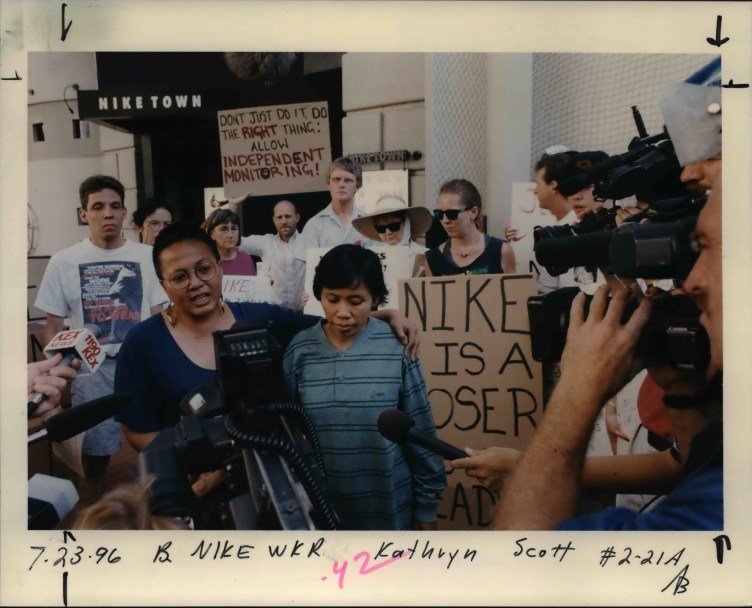

Around the time the lawsuit concluded, in July 1996, Cicih walked onto Nike’s suburban campus near Beaverton, Oregon, and demanded a meeting with the company’s co-founder.

“I’m here to meet with Phil Knight,” she said, according to The Oregonian’s coverage of her visit. “I want to ask him to consider the plight of Indonesian workers.”

Cicih had stayed in touch with Ballinger. He helped bring her to the United States to put pressure on Nike, one of four such visits she made to the country.

Knight refused to see her.

A week before Cicih arrived in Beaverton, Knight wrote a letter to her trip’s organizers, saying he was “sympathetic” to her case but preferred to meet with people “interested in constructive, proactive solutions, not those who announce their intentions through news conferences and mean-spirited media campaigns.”

He defended Nike’s response to problems at Cicih’s factory, saying Nike had worked to correct them.

“The factory where Ms. Sukaesih worked has been under new Indonesian management for two years, the grievances have been addressed and the minimum wage is in force,” Knight wrote. “In our view, this is an example of the benefit Nike brings in upgrading labor practices in emerging market societies.”

After she made her request to meet with Knight, a “trio of beefy Nike security guards” escorted Cicih off Nike’s campus and local sheriff’s deputies asked her to leave the premises, according to The Oregonian’s coverage.

Roughly a week later, Knight sat across the table from President Bill Clinton at the White House to talk about labor reforms, according to records obtained from the Clinton Presidential Library. Knight then stood in the Rose Garden behind Clinton as the president announced a sweeping effort to address sweatshop conditions in overseas factories.

“While I think that we have been good citizens within our industry, I think there’s clearly a lot more that we can do, that we can indeed be better,” Knight said in his brief remarks.

The meeting with Clinton led to the creation of the Fair Labor Association, one of several groups that monitor factory working conditions.

Knight publicly committed to specific sweatshop reforms in a 1998 speech at the National Press Club. Knight announced six changes, including heightened indoor air quality standards, increased factory monitoring and raising the minimum age in footwear factories to 18.

He didn’t say anything about raising wages.

“You Have to Fight”

These days, Nike factory workers in Indonesia told The Oregonian/OregonLive, the kind of forced overtime that sparked Cicih’s desire to “rebel” is nonexistent. They also said Nike lived up to Knight’s commitment to get underage workers out of Indonesian factories.

But they said problems remain.

In interviews, they criticized the auditing process, the linchpin of the factory monitoring system that Nike helped pioneer. Workers said factories know in advance when auditors will arrive. At one factory, workers said safety equipment had been distributed on the eve of an audit.

“The best time to work at a Nike factory is when it’s being audited,” a worker said.

Workers said more rigorous and consistent auditing would catch problems with safety and sexual harassment, which they said remain persistent.

Asked about the workers’ description of factories prepping for planned audits, Nike said that it conducts unannounced audits in addition to those that are scheduled in advance, and that these are supplemented by “worker engagement and well-being surveys,” among other efforts.

“When issues are brought to our attention, through any mechanism, we work with suppliers to validate, identify root causes and implement comprehensive remediation processes,” Nike said.

Nike’s most recent disclosures say 87% of the 623 suppliers it audited in fiscal year 2024 at least met the company’s basic code of conduct requirements. The company also disclosed a factory injury rate significantly below its peers. Less than 1% of code of conduct violations related to harassment and abuse, according to the disclosure.

Workers and union leaders also say their No. 1 concern — low wages — has not been addressed. Many said they work second jobs to make ends meet.

“One job isn’t enough,” Keady said. “They’re not getting a second job because they want to send their kid to a really good private school or they want to buy a home in a great neighborhood. They’re getting a second job because they can’t afford three meals a day for their family.”

Cicih also has struggled.

After her lawsuit against the factory that once employed her, she had the option to return, but she declined. She thought the environment would be uncomfortable because of her history as an organizer.

She did some volunteer work as a labor organizer. Some other organizers encouraged her to set up a small business.

Those efforts never panned out. She moved back to her hometown of Menes in 2018.

A sister on whom Cicih depended financially died during the pandemic. Cicih opened a roadside food stall and sold vegetable salad and gado gado, a type of Indonesian dish, but it didn’t go well.

She gets by on donations from American do-gooders, including Keady. She grows some of her own food. She doesn’t have a pension or savings.

“Nothing,” she said.

But she’s resolute.

“You have to do this,” she said, reflecting on her years as an activist. “You have to fight.”

#Cicih #Sukaesih #Crusaded #Nike #Factory #Workers #Rights #Indonesia #ProPublica