Fourteen-year-old Ariana Velasquez had been held at the immigrant detention center in Dilley, Texas, with her mother for some 45 days when I managed to get inside to meet her. The staff brought everyone in the visiting room a boxed lunch from the cafeteria: a cup of yellowish stew and a hamburger patty in a plain bun. Ariana’s long black curls hung loosely around her face and she was wearing a government-issued gray sweatsuit. At first, she sat looking blankly down at the table. She poked at her food with a plastic fork and let her mother do most of the talking.

She perked up when I asked about home: Hicksville, New York. She and her mother had moved there from Honduras when she was 7. Her mother, Stephanie Valladares, had applied for asylum, married a neighbor from back home who was already living in the U.S., and had two more kids. Ariana took care of them after school. She was a freshman at Hicksville High, and being detained at the Dilley Immigration Processing Center meant that she was falling behind in her classes. She told me how much she missed her favorite sign language teacher, but most of all she missed her siblings.

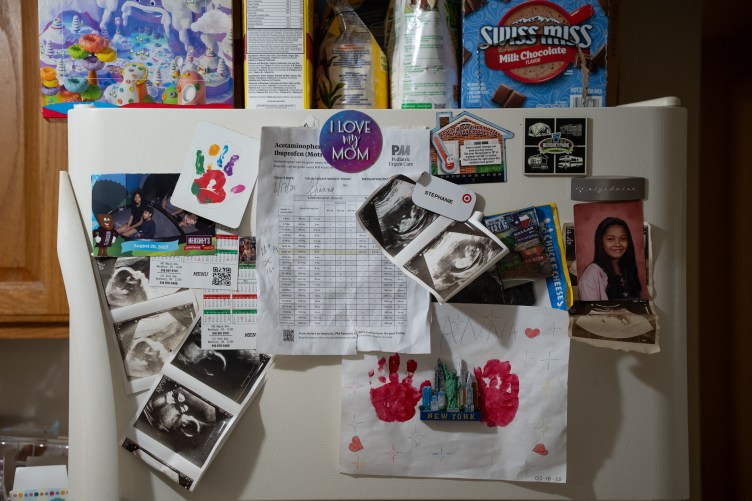

I had previously met them in Hicksville: Gianna, a toddler who everyone calls Gigi, and Jacob, a kindergartener with wide brown eyes. I told Ariana that they missed her too. Jacob had shown me a security camera that their mom had installed in the kitchen so she could peek in on them from her job, sometimes saying “Hello” through the speaker. I told Ariana that Jacob tried talking to the camera, hoping his mom would answer.

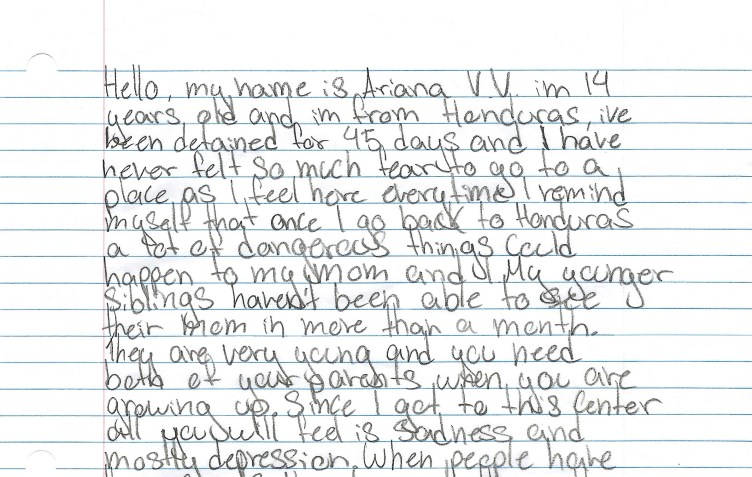

Stephanie burst into tears. So did Ariana. After my visit, Ariana wrote me a letter.

“My younger siblings haven’t been able to see their mom in more than a month,” she wrote. “They are very young and you need both of your parents when you are growing up.” Then, referring to Dilley, she added, “Since I got to this Center all you will feel is sadness and mostly depression.”

Dilley, run by private prison firm CoreCivic, is located some 72 miles south of San Antonio and nearly 2,000 miles away from Ariana’s home. It is a sprawling collection of trailers and dormitories, almost the same color as the dusty landscape, surrounded by a tall fence. It first opened during the Obama administration to hold an influx of families crossing the border. Former President Joe Biden stopped holding families there in 2021, arguing America shouldn’t be in the business of detaining children.

But quickly after returning to office, President Donald Trump resumed family detentions as part of his mass deportation campaign. Federal courts and overwhelming public outrage had put an end to Trump’s first-term policy of separating children from parents when immigrant families were detained crossing the border. Trump officials said Dilley was a place where immigrant families would be detained together.

As the second Trump administration’s crackdown both slowed border crossings to record lows and ramped up a blitz of immigration arrests all across the country, the population inside Dilley shifted. The administration began sending parents and children who had been living in the country long enough to lay down roots and to build networks of relatives, friends and supporters willing to speak up against their detention.

If the administration believed that putting children in Dilley wouldn’t stir the same outcry as separating them from their parents, it was mistaken. The photo of 5-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos from Ecuador, who was detained with his father in Minneapolis while wearing a Spider-Man backpack and a blue bunny hat, went viral on social media and triggered widespread condemnation and a protest by the detainees.

Weeks before that, I had begun speaking to parents and children at Dilley, along with their relatives on the outside. I also spoke to people who worked inside the center or visited it regularly to give religious or legal services. I had asked Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials for permission to visit but got a range of responses. One spokesperson denied my request, another said he doubted I could get formal approval and suggested I could try showing up there as a visitor. So I did.

Since early December, I’ve spoken, in person and via phone and video calls, to more than two dozen detainees, half of them kids detained at Dilley — all of whose parents gave me their’ consent. I asked parents whether their children would be open to writing to me about their experiences. More than three dozen kids responded; some just drew pictures, others wrote in perfect cursive. Some letters were full of age-appropriate misspellings.

Among them was a letter from a 9-year-old Venezuelan girl, named Susej Fernández, who had been living in Houston when she and her mother were detained. “I have been 50 days in Dilley Immigration Processing Center,” she wrote. “Seen how people like me, immigrants are been treated changes my perspective about the U.S. My mom and I came to The U.S looking for a good and safe place to live.”

Susej Fernández, 9, Shares Her Daily Struggles in Detention

A 14-year-old Colombian girl, who signed her name Gaby M.M. and who a fellow detainee said had been living in Houston, wrote a letter about how the guards at Dilley “have bad manner of speaking to residents.” She wrote, “The workers treat the residents unhumanly, verbally and I don’t want to imging how they would act if they where unsupervised.”

Nine-year-old Maria Antonia Guerra, from Colombia, drew a portrait of herself and her mother wearing their detainee ID badges. A note on the side said, “I am not happy, please get me out of here.”

Some of the kids I met spoke English as well as they did Spanish.

When I asked the kids to tell me about the things they missed most from their lives outside Dilley, they almost always talked about their teachers and friends at school. Then they’d get to things like missing a beloved dog, McDonald’s Happy Meals, their favorite stuffed animal or a pair of new UGGs that had been waiting for them under the Christmas tree.

They told me they feared what might happen to them if they returned to their home countries and what might happen to them if they remained here. Thirteen-year-old Gustavo Santiago said he didn’t want to go back to Tamaulipas, Mexico. “I have friends, school, and family here in the United States,” he said of his home in San Antonio, Texas. “To this day, I don’t know what we did wrong to be detained.” He ended with a plea, “I feel like I’ll never get out of here. I just ask that you don’t forget about us.”

Around 3,500 detainees, more than half of them minors, have cycled through the center since it reopened, more than the population of the town of Dilley itself. Although a long-standing legal settlement generally limits the time children can be held in detention to 20 days, a data analysis by ProPublica found that about 300 kids sent to Dilley by the Trump administration were there for more than a month. The administration in legal filings has said the agreement from 1997 is outdated and should be terminated because there are new statutes, regulations and policies that ensure good conditions for immigrant minors in detention.

Habiba Soliman, 18, told me she had been detained for more than eight months with her mom and four siblings, ranging in age from 16 to 5-year-old twins, after her father was charged for an alleged antisemitic attack in June at rally in Boulder, Colorado, supporting the Jewish hostages who were being held in Gaza. Their father, Mohamed Soliman, pleaded not guilty to federal and state charges. Authorities have said they are investigating whether his wife and her children provided support for the attack. They deny knowing anything about it and an arrest warrant reports that he told an officer he never talked to his wife or family about his plans.

Despite Trump’s promise to go after violent criminals, the vast majority of adults detained at Dilley over the last year had no criminal record in the United States. Some of the parents I spoke to had overstayed visas. Many had filed applications for asylum, had married U.S. citizens or had been granted humanitarian parole and were detained when they voluntarily showed up for appointments at ICE offices. They said that it was unfair to arrest them, and that detaining their children was just plain cruel.

There were children in Dilley who were so distraught they cut themselves or talked about suicide, several mothers told me. Recently, two cases of measles were discovered in the center. Federal officials said they quarantined some immigrants, and attorneys said ICE cancelled in-person legal visits until Feb. 14 as a safety precaution.

Read More Letters From Kids Detained at Dilley

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE, said in a statement that all detainees at Dilley are “being provided with proper medical care.” DHS did not respond to questions about individual detainees but said that all “are provided with 3 meals a day, clean water, clothing, bedding, showers, soap, and toiletries” and that “certified dieticians evaluate meals.” Detained parents are given the option for their families to be deported together, or they can have their children placed with another caregiver, the statement said.

CoreCivic said that Dilley, like its other facilities, is subject to multiple layers of oversight to ensure full compliance with policies and procedures, including any applicable detention standards.

Moms told me that their kids had lost their appetites after finding worms and mold on their food, had trouble sleeping on the facility’s hard metal bunk beds in rooms shared by at least a dozen other people, and were constantly sick.

“The shock for my daughter was devastating,” Maria Alejandra Montoya from Colombia wrote in an email to me about her daughter Maria Antonia. “Watching her adapt is like watching her wings being clipped. Hearing other children fight over card games at the tables makes me feel like we are not mothers and children, but inmates.”

Life Inside

Alexander Perez, a 15-year-old from the Dominican Republic, told me about going to school at Dilley. He said classes included kids from mixed age groups, and each class allowed only 12 students and lasted for just one hour. Slots were assigned on a first-come-first-served basis. Children would line up, hoping to get in. The staff leading the class would distribute handouts and worksheets to those who made it inside.

Alexander Perez complained that the lessons were usually meant for kids who were younger than him, so he found them boring. But because there wasn’t much else to do, he used to go whenever he could, until an instructor turned a social studies lesson into what felt like an interrogation about immigration policy.

“If we have recreational activities and classes designed to help us disconnect from what we’re experiencing here, why the need to ask ourselves these questions?” he said during a video call with me. “I didn’t think that was right.”

Alexander Perez, 15, Shares His Advice for Other Dilley Detainees

He, his mother and his 14-year-old brother, Jorge, said they had been detained while traveling from Los Angeles to Houston when the bus they were on was stopped by immigration agents who checked everyone’s status. They’d been in Dilley for four months by the time we spoke. His mother, Teresa, told me she was in the process of appealing a judge’s denial of her asylum petition, which might explain why it was a touchy subject for Alexander when it came up in class. He told me that after he gave up on attending classes at Dilley, he played basketball in the recreation area and watched a lot of Spanish soap operas on TV. Jorge, who celebrated his birthday in December at Dilley with a tiny cake made from vanilla commissary cookies, spent most of the day sleeping.

DHS said in its statement that “children have access to teachers, classrooms, and curriculum booklets for math, reading, and spelling.”

Boredom was a theme that ran through many of the letters from children at Dilley. “They told me I could only be here 21 days but I have already spent more than 60 days waking up eating the same repeated meals,” wrote a 12-year-old Venezuelan girl who signed her letter Ender, and who a fellow detainee said had settled with her mother in Austin, Texas. She wrote that when she felt sick and went to the doctor, “the only thing they tell you is to drink more water and the worst thing is that it seems like the water is what makes people sick here.”

Ariana expressed similar concerns in her letter. She wrote, “If you need medical attention the longest you have to wait is 3 hours, but to get any medicine, pill, anything it takes a while, there are various viruses people are always sick. Serious situations happen and the officers can’t take them serious enough there are no consecuenses, they don’t care.”

Bad Food, Insufficient Medicine

The lack of reliable medical care was perhaps the most serious concern parents and children spoke about in their interviews with me. The Texas-based nonprofit advocacy organization RAICES, which provides legal representation to many families at Dilley, said in a recent court declaration that its clients had raised concerns about insufficient medical care on at least 700 occasions since August 2025. The organization reported, “Children with medical complaints frequently experience delays, dismissals, or lack of follow-up.”

Kheilin Valero from Venezuela, who was being held with her 18-month-old, Amalia Arrieta, said shortly after they were detained following an ICE appointment on Dec. 11 in El Paso, Texas, the baby fell ill. For two weeks, she said, medical staff gave her ibuprofen and eventually antibiotics, but Amalia’s breathing worsened to the point that she was hospitalized in San Antonio for 10 days. She was diagnosed with COVID-19 and RSV. “Because she went so many days without treatment, and because it’s so cold here, she developed pneumonia and bronchitis,” Kheilin said. “She was malnourished, too, because she was vomiting everything.”

Gustavo Santiago, the 13-year-old boy who’d been living in Texas, said he has been sick several times since he and his mom were detained on Oct. 5 of last year at a Border Patrol checkpoint. His mom, Christian Hinojosa, said that when Gustavo had a fever, the medical staff told her he was old enough for his body to fight it off without medication, so she sat up with him all night, draping him in cold compresses. She had to take him to the infirmary for a skin rash that she believed was caused by poor water quality at the center. She said he has also experienced stomach pain and nausea, which she blamed on unsanitary food preparation.

Among logs we obtained of calls made to 911 and law enforcement about the facility since it began accepting families again last spring, I found pleas for help for toddlers having trouble breathing, a pregnant woman who passed out and an elementary-school-aged girl having seizures. Local authorities were also called in for three cases of alleged sexual assault between detainees.

DHS said in its statement, “No one is denied medical care.”

CoreCivic said that health and safety is a top priority for the company and that detainees at Dilley are provided with a continuum of health care services, including preventative care and mental health services. The company said its medical staff “meet the highest standards of care” and said the facility works closely with local hospitals for any specialized medical needs.

The Kids of Dilley

Reporter Mica Rosenberg talked with dozens of detainees at Dilley, who shared their experiences in letters, videos, phone calls and voice memos.

Torn From Their Lives

Ariana and her mother, Stephanie, were detained on Dec. 1, when they went for one of their regular check-ins at an ICE office in New York City’s Federal Plaza, which are required as they wait for a decision on their asylum case. Stephanie had come to the U.S. with experience working as an accountant and, after securing her work permit, she had finally found a job at a local import business where she could put that experience to use. They had been regularly checking in with ICE for years without incident. But after mom and daughter showed up for their 8 a.m. ICE appointment, they were told they couldn’t leave this time and were on a plane to Dilley by 6 that evening, without being given a chance to call their family. “Since the day my mom and I get detained in Manhattan NY, my life was instanly paused,” Ariana wrote in her letter from detention after our meeting. “All kids are being damage mentally, they witness how the’ve been treated.”

A 7-year-old Honduran girl named Diana Crespo was living in Portland, Oregon, when she and her parents, Darianny Gonzalez and Yohendry Crespo, were detained outside a hospital where they’d taken Diana for emergency care. The family had been granted humanitarian parole after entering the United States in 2024 and then applied for asylum when Trump revoked the parole program, saying that Biden had used it to allow immigrants to pour into the country at record levels. She said their active asylum case didn’t stop the immigration agents who intercepted them outside the emergency room from detaining them.

Maria Antonia Guerra, the 9-year-old from Colombia, told me that the 10-day vacation to Disney World that she had planned with her mother and stepdad turned into more than 100 days at Dilley. She’d flown into Florida from Medellin, Colombia, where she lived with her grandmother, with a Cruella de Vil costume in her suitcase. Her mother, Maria Alejandra Montoya, was living in New York and had overstayed her visa, but had since married a U.S. citizen and was just waiting for her green card to be approved. Maria Antonia traveled regularly back and forth to the U.S. on a tourist visa, and Maria Alejandra had flown down to meet her at the airport. Immigration agents intercepted them and flew them to Texas. They both told me that it felt like a kidnapping.

“I am in a jail and I am sad and I have fainted 2 times here inside, when I arrived every night I cried and now I don’t sleep well,” Maria Antonia, who wears thick glasses, wrote to me. “I felt that being here was my fault and I only wanted to be on vacation like a normal family.”

Released but Still Afraid

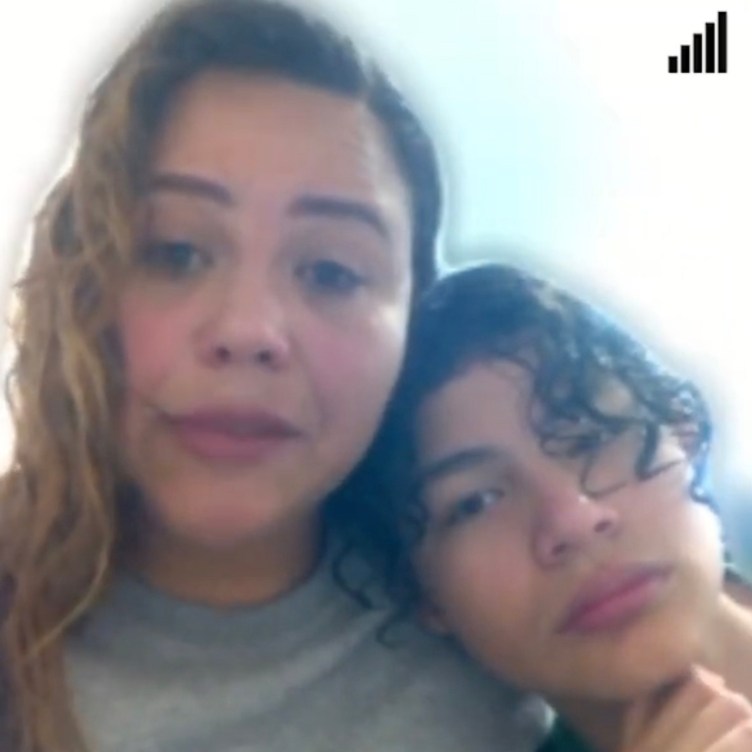

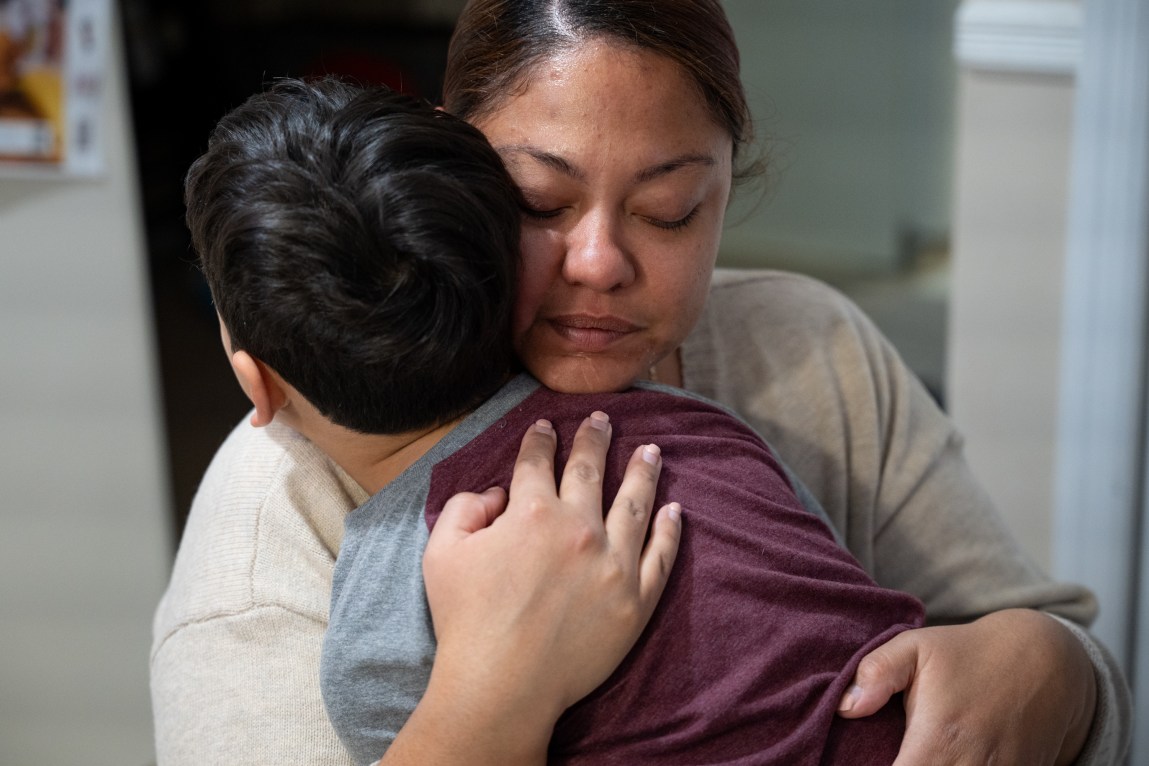

In January, shortly after my visit to Dilley, ICE released some 200 people all at once, without explanation. Among them were Ariana and her mom.

The releases came as such a surprise that Stephanie said another woman began screaming and refused to let go of her bunk, fearing she was about to be deported back to Ecuador. Stephanie was fitted with an ankle monitor, and she and Ariana were dropped off in Laredo, Texas, where they scrambled to buy a plane ticket to LaGuardia in New York.

On Jan. 22, two days after her release, I met Stephanie again, this time holding Gigi as she showed up for her first ICE check in at an office near her home. She had been so nervous that she got lost on the way to the appointment. She was given a series of instructions and shown videos that explained the purpose and cadence of her regular check-ins. She’d have one every month at the office, and every two months she would be visited at her home.

Jacob had initially refused to go to school because he was afraid his mother and sister wouldn’t be there when he came home, but she’d finally gotten him to go by promising every morning that she’s not leaving again.

Ariana went back to school a few days later. Her English teacher immediately hugged her and sobbed, “We really missed you.”

I called Ariana last Wednesday to check in on her. She was helping Jacob with his homework, but she took a break to give me an update. There are a lot of other immigrants at her school, but she had only told her close friends, who she sits with at lunch, about the reason for her prolonged absence. When other people asked, she just said, “I had to go to Texas for something.”

She says she’s trying to put the ordeal behind her, but the toll is real.

Her mother lost her job because her boss is uncomfortable employing someone with an ankle monitor. And Ariana worries about her. She also worries about the people she met back at Dilley. Days after I asked DHS about several families mentioned in this story, five of them were released: Gustavo and his mom, Christian; Teresa and her sons, Alexander and Jorge; Kheilin and her baby, Amalia; Darianny and her daughter, Diana. Maria Antonia and her mom, Maria Alejandra, were returned to Colombia. Others are still detained. Ariana said, “I wish they got out because they shouldn’t be there any longer.”

Before we hung up, Ariana said something that suggested her youthful optimism hadn’t been entirely broken. She’d found that she’d gotten better at playing volleyball at Dilley and now plans to try out for her school team.

For this story, ProPublica analyzed federal data on ICE detentions released through the Deportation Data Project. The data contains records for immigrant arrests and detentions going through October of 2025.

#Children #Describe #Life #Dilley #ICE #Detention #Center #ProPublica