Wrapped in a flashy fur coat she’d found at a thrift store for the occasion, Hannah Goetz blew out the candles on her favorite red velvet cheesecake. It was her 21st birthday. The celebration with her family that evening in February 2023 was a milestone not just for her age, but because she was alive.

Three and a half years before, her lungs had collapsed from cystic fibrosis. She was saved by a double-lung transplant that had been allowing her to breathe deeply. Hannah had slowly worked her way back to stable health, overcoming infections and, every day, taking a crucial medication to protect her donated lungs from rejection. Her doctors were optimistic.

Hannah had been feeling well enough to sing karaoke, work as a nanny while taking college classes and begin her first adult relationship, with a Navy sailor. Her 21st birthday gift from her mom was a trip to Nashville, Tennessee, where the two of them and their friends could explore the city’s music scene and cavort in its bars.

Just days after her birthday, though, she was back in the hospital. She’d been feeling her chest tighten, and she struggled for air. By March, Hannah felt as if she were breathing through a straw. Tests showed she was taking in less than half the oxygen of a healthy person.

One of the first questions came from her transplant team’s pharmacist, who had overseen her medications since her operation.

“Did the tacrolimus pills you take change?” he asked.

Most people have never heard of tacrolimus. But to anybody who has received a transplant, it’s nothing short of a miracle. The medication prevents organ rejection. Without tacrolimus, a simple capsule taken twice a day, cells in the blood identify the transplanted organ as a foreign invader and treat it like an infection, trying to rid the body of it. That attack can be fatal.

A team of Japanese scientists discovered tacrolimus in the 1980s, in a fungus found in the soil of a lush, purple-hued mountain north of Tokyo.

Along with another similar drug, tacrolimus radically improved the long-term prospects of transplant patients. The chances that a donated organ would still work after a year roughly doubled for those who used the drugs. Recipients of kidney, heart and liver transplants started living years longer. So did lung patients, but the challenges of those transplants meant the increases in lifespan were smaller.

By the numbers, if Hannah made it past her first year, she could expect her new lungs to give her nine more years of life.

Hannah was in fourth grade in 2012 when doctors figured out that her regular bouts of bronchitis and her struggle to gain weight were caused by cystic fibrosis, a genetic disease that leads to mucus building up in the lungs and other organs. The disease is ultimately fatal.

Ten-year-old Hannah sat listening for hours as a medical team explained the diagnosis to her and detailed how it was treated. The doctors managed to avoid any discussion of mortality, and it wasn’t until Hannah got home that she found the answer she sought online. At that time, the median lifespan was less than 40 years. Mom, she asked, did you know I won’t live as long as most people?

Holly Goetz, a high school teacher who was newly divorced and shouldered almost all of her daughter’s care, tried to reassure Hannah. Her case wasn’t severe, she told her daughter. And new advancements could improve the outlook.

Hannah didn’t dwell on the diagnosis, and she managed to keep up with peers in her Isle of Wight, Virginia, school, playing soccer and singing in musicals. Like any tween, she documented every moment of her life in a series of selfie videos. In one from fourth grade, she chatted to the camera as if she were a jocular TV host, capturing the twice-a-day event when she wore a device that looked like a life preserver and shook her chest to break up the mucus in her lungs. “Here I am, vibrating, whooo!” she trilled in rhythm with the pink vest. She ended the video, “See you next time on Vest Treatment with Hannah.”

Sometimes, she also needed a feeding tube hooked up to her stomach at night to ensure her body absorbed enough calories. And there were occasional two-week stints at the local children’s hospital for a course of antibiotics.

Still, she graduated high school a year early, as a 17-year-old, in June 2019. That month, sporting purple streaks in her hair, she’d gone with her family to the Caribbean to celebrate her achievement. She was looking forward to attending Longwood University, a couple of hours west from her hometown.

Hannah, whose signature pose was sticking her tongue out, was relatively healthy during her teen years despite having cystic fibrosis — at least, until she was 17.

One afternoon not long after returning from the trip, Hannah told her mom she was feeling sick. Holly packed up, thinking they were headed to the hospital for a standard “tune up.”

This time, though, Hannah quickly went from sitting up in her hospital bed, mouthing along with the “Frozen” song “Do You Want to Build a Snowman?” to a ventilator in the pediatric ICU. She had pneumonia, which was filling her already clogged lungs with even more fluid. Hannah also had an infection from a rare bacteria that had caused sepsis, a type of potentially lethal inflammation. Before Holly could process what was happening, Hannah was in an ambulance, being transferred three hours north to the better equipped Inova Fairfax Medical Campus.

The doctors said the prognosis was dire: Hannah’s lungs were too damaged to recover, and she needed a double-lung transplant. But the infection was proving insurmountable. Hannah was stuck on the wrong side of an agonizingly thin line: A patient needs to be severely compromised to qualify for a replacement organ; but if they’re too gravely ill, they’re ineligible.

The transplant team proposed something bold. The only way to give Hannah a chance, they said, was to remove both of her lungs — without knowing whether they’d find new ones for her — in the hopes that if they went, so too would the infection. That would clear the way for her to be added to the transplant list.

For four days, Hannah lay unconscious in the ICU with no lungs while machines pumped her heart and tubes the size of garden hoses circulated oxygen through her body. Holly curled her lanky frame into a chair by Hannah’s bedside every night. She prayed first that the infection would clear and then, later, that a lung donor would be found.

The risky move was a success. When Hannah awoke in August, fully conscious for the first time in three weeks, she had no memory of what had happened. Her mom told her everything was going to be OK; she had new lungs.

Hannah spent 67 days recuperating in the hospital. At first, she could only take a few tentative steps from her bed with the aid of both a walker and a nurse. She ultimately strode out of the hospital with her arms flung above her head in triumph. Doctors marveled, saying that Hannah had been saved by her youth and surprisingly healthy body.

Medications are so central to recovery from a transplant that the federal government requires hospitals to assign a pharmacy expert as part of a patient’s team. For Hannah, that person was Adam Cochrane, a specially trained transplant pharmacist with two decades of experience who worked exclusively with lung- and heart-transplant patients.

Cochrane, who has a calm, measured disposition, tried not to overwhelm Hannah and her mom as he taught them about the lineup of pills Hannah now needed to take. The daily regime was critical. She can’t live without these medications, he told them. Hannah would need to take tacrolimus twice a day at the same time every day — for the rest of her life.

Tacrolimus is part of a special category of drugs that work only if the dose is calibrated within a very narrow range. Any amount outside that window can be dangerous, particularly for lung transplant patients, who face high rates of rejection. To make sure Hannah was getting the correct dose of tacrolimus, Inova would test her blood every other week to start and then once a month after that. (Inova said that it doesn’t comment on individual cases but that it “collaborates closely with transplant recipients to ensure they access appropriate medications to maximize the likelihood of a successful outcome.”)

There’s no formula that tells Cochrane what dosage each patient needs, so he tinkered to find the sweet spot. He thought of it as a teeter-totter. Too much tacrolimus and the immune system would dip too weak to ward off infection. Too little tacrolimus, and the immune system would tip too strong and attack the transplanted organ. Cochrane knew that a steep tip in either direction was potentially catastrophic.

For years, tacrolimus was made by one company, now called Astellas, which had discovered and patented the drug. When generic versions arrived 15 years later, none behaved in the body exactly like the original tacrolimus or like one another. To make a generic, most companies have to reverse engineer the brand drug; there’s no recipe to follow. Each generic is a distinct formula made in a distinct way.

As with all generics, the tacrolimus versions approximated the original within a broad range set by the Food and Drug Administration. In general terms, it’s how much a generic can differ from the original brand in the amount of the key ingredient that reaches the relevant part of the body and when.

As the FDA considered the first generic version of tacrolimus in the mid-2000s, the agency had to decide whether there should be stricter rules for generic versions of the small number of drugs like tacrolimus that require such precision dosing. Canada and the European Union both adopted tighter standards. Those governments essentially halved the range considered to be a match for the brand drug.

But the U.S. continued with a one-size-fits all approach, allowing the looser standards that treated tacrolimus like any other generic drug. The agency said in 2009 that it was confident that its “method for approving generic tacrolimus uses appropriate bioequivalence standards.”

The FDA approved the first generic version of tacrolimus that same year. In May 2010, one made by an Indian generics company called Dr. Reddy’s was approved. The next year, so was one made by another Indian company called Intas, whose U.S. brand is called Accord.

In all, six generics were greenlit before the FDA reversed course and decided in 2012 that tacrolimus should, after all, be made under tighter criteria. But the rule applied only to companies newly approved to sell a generic version of tacrolimus. The agency did not require Dr. Reddy’s, Accord and the others already on the market to meet the new standard. The agency stated later in a public filing that it doesn’t retroactively apply new standards to existing products.

Almost from the beginning, some transplant doctors had raised concerns that patients on Dr. Reddy’s tacrolimus were faring worse than those on other generics. The Cleveland Clinic was so alarmed that it banned Dr. Reddy’s generic for its transplant patients in 2013. Later, at the Tulane Transplant Institute, doctors found that patients taking generic tacrolimus by any drugmaker had a higher chance of organ rejection, and the hospital decided to use only the brand drug.

At Inova, Cochrane had noticed irregular fluctuations in patients taking Dr. Reddy’s as well as early signs of organ rejection. “Omg! … Another [patient], victim of Dr Reddy,” an Inova nurse wrote in a 2019 email obtained by ProPublica.

Holly knew none of this when she picked up her daughter’s tacrolimus at the local Kroger grocery store after Hannah’s discharge in the fall of 2019. (Kroger didn’t respond to requests for comment.) Unlike with Hannah’s medical care, where Holly could research and choose a doctor or hospital, the brand of generic tacrolimus Hannah received was out of her hands. She would get whichever one that pharmacy happened to have in stock.

Inova’s transplant team had typed, in the electronic prescription that it sent to Kroger, “do not dispense Dr. Reddy.” But that’s what Hannah received.

Just months after Hannah was discharged from the hospital with her new lungs, COVID-19 shut down the world. Holly couldn’t believe she had to be on guard against yet another threat, one so dangerous to her immunocompromised daughter. Lungs are among the trickiest organs to protect, in part because they draw in germs in the air with every breath.

Despite those threats, Holly found a kind of appreciation for the moment. The pandemic meant she could keep 18-year-old Hannah, otherwise eager to leap back into life, tucked away at home during her perilous first year after the transplant. When she’d first been discharged, Hannah had shown a streak of teenage rebelliousness. She was quick to drive off in the pumpkin-colored Jeep Holly had given her and get tattoos and piercings, risking infections that transplant patients were supposed to avoid.

Hannah lived through the COVID-19 quarantine with her mom and younger brother in their modest clapboard house on a neat suburban street. The three of them, and their newly adopted St. Bernard-poodle mix, Miracle, made dance videos together, and at night, Hannah curled up to sleep in her mom’s bed rather than head to her own room.

That year, Hannah’s lung function improved to normal levels as her body grew stronger. When the pandemic began to recede in 2021 and Hannah ventured out more, Holly remained diligent about her daughter’s tacrolimus, making sure she took it every morning and night. Holly insisted Hannah either send a video of her taking the medication or FaceTime while she did so.

Cochrane and the team observed fluctuations in Hannah’s tacrolimus levels. They’d adjust her dosage to try to keep her at the optimal amount. Cochrane concluded that Hannah was perhaps not taking her medication at the same time every day, he told ProPublica. That’s not unusual for young patients. Her adherence to other drugs unrelated to rejection had proved spotty. Hannah wasn’t always diligent about taking the enzymes she needed to aid her pancreas and keep her weight up, and she declined to continue a new cystic fibrosis medication that she didn’t feel was giving her results.

But Cochrane said he didn’t think any sloppiness with her tacrolimus meds fully explained the wild swings he often saw when she was admitted to the hospital to treat an infection. His experience with other patients had convinced him that the generic versions of tacrolimus varied significantly, enough to harm the health of a patient.

During one inpatient stay at Inova in August 2021, Cochrane gave Hannah the same dose of tacrolimus she took at home. But he used a different generic from the hospital’s pharmacy. Cochrane expected to see steady levels of the drug in Hannah’s system. Instead, the amount of tacrolimus was much higher than it had been. He said he couldn’t remember why he didn’t ask Hannah about which brand of generic she was using.

Well before Hannah began taking the drug, there had been concerns inside the FDA about whether tacrolimus generics were being made correctly, according to an agency drug official who was there at the time. The manufacturing process for tacrolimus is particularly complex.

The medical community had kept pushing the FDA to do more to verify the effectiveness of tacrolimus generics, and in 2013 the agency acquiesced and commissioned a study. That study, which was completed in 2015 and included Dr. Reddy’s, identified a problem with one generic: the version made by Accord. It didn’t mimic the brand drug as it was supposed to.

But the agency decided those results were not definitive. The FDA didn’t make the findings public, and Accord’s tacrolimus remained on the market.

In 2021, an FDA-commissioned follow-up study showed unequivocally that Accord was not equivalent to the brand drug, potentially delivering too much medication to the patient. But once again, the FDA did not warn the public. Accord continued to be sold as usual.

A few months later, in December 2021, Kroger began filling Hannah’s prescription with Accord’s version of tacrolimus.

At first, the new generic seemed to have no negative effect. Hannah had fewer bouts of infection than the year before. She was feeling the best she had since the operation, faring well enough that Holly thought it was OK to leave her for the first time and go on a cruise.

That year, in July 2022, Hannah marked her three-year transplant anniversary on Instagram with a close-up picture of her “bad ass scars.” They were a sort of tattoo she hadn’t chosen, but, as she wrote, they “will always remind me that I got a second chance.”

Both Hannah and her mom were taken by surprise when Hannah’s breaths became shallow around the time of her 21st birthday in 2023.

“i wish i was out and about with friends and family enjoying the weather but unfortunately my reality has been me cooped up in a hospital room,” she posted to Instagram in March. “I put on a brave face for all my loved ones, but deep down it affects me everyday.”

Hannah celebrated her “lungiversary” one year by taking the roof and doors off her orange Jeep and convincing her cousin to get matching Saturn and moon tattoos.

The next month, tests confirmed that Hannah’s lung function had declined precipitously. If she’d been breathing through a soda straw before, now it was closer to the thin red ones used to stir coffee.

Cochrane asked what brand of tacrolimus she was taking. He always had to sleuth a bit to figure out what might be going on; perhaps a patient had chronic digestive problems or their diet had changed, affecting the absorption of tacrolimus. He was most concerned that a patient had been on Dr. Reddy’s. Cochrane was not suspicious of Accord at the time; the FDA hadn’t made its study results public.

Holly went home after the conversation with Cochrane and scoured her medicine cabinets. It was the first time she’d ever had a reason to look at the manufacturer. Cochrane had trusted pharmacies to follow Inova’s instructions, and so he hadn’t previously warned Holly to avoid Dr. Reddy’s. Sure enough, Hannah had old bottles labeled Dr. Reddy’s. Cochrane told Holly to throw them away.

For more than three years, Hannah had exclusively taken tacrolimus manufactured by companies that had alarmed either doctors, pharmacists or the FDA. Cochrane would later wonder if there had been a cumulative effect — chronic rejection is “sneaky and slow” — and Hannah had now reached a tipping point. Her donated lungs were failing.

Hannah’s mood darkened as her decline accelerated. In April 2023, back at her local hospital yet again, she snapped at the nurses. Everyone was always telling her how strong she was, she fumed. She wanted out of that room. When she counted the days she’d been home rather than hospitalized since late January, she realized it had been only 20.

“I don’t want to do this again,” Hannah told her longtime respiratory therapist.

Anxiety gripped her at all hours. She couldn’t breathe.

That month, a biopsy had confirmed that her body was rejecting her lungs, precisely what tacrolimus was supposed to prevent. The damage was irreversible.

“Once again, they’ve decided i need new lungs,” Hannah wrote on Instagram. “It’s happening a lot sooner than anyone expected.”

Hannah checked into Inova in June with the expectation that she would have a second lung transplant. But as she got increasingly sick, she spent the next five weeks being moved between the transplant wing and the ICU two floors below. Holly was vigilant by her side. When Hannah lashed out because there was a tear in her pink security blanket, the one she’d had every time she was hospitalized since she was 10, Holly paid someone double to patch it in one hour. She followed doctors into the hallway after they checked on Hannah. Her daughter had done everything they’d asked of her. When was she getting new lungs?

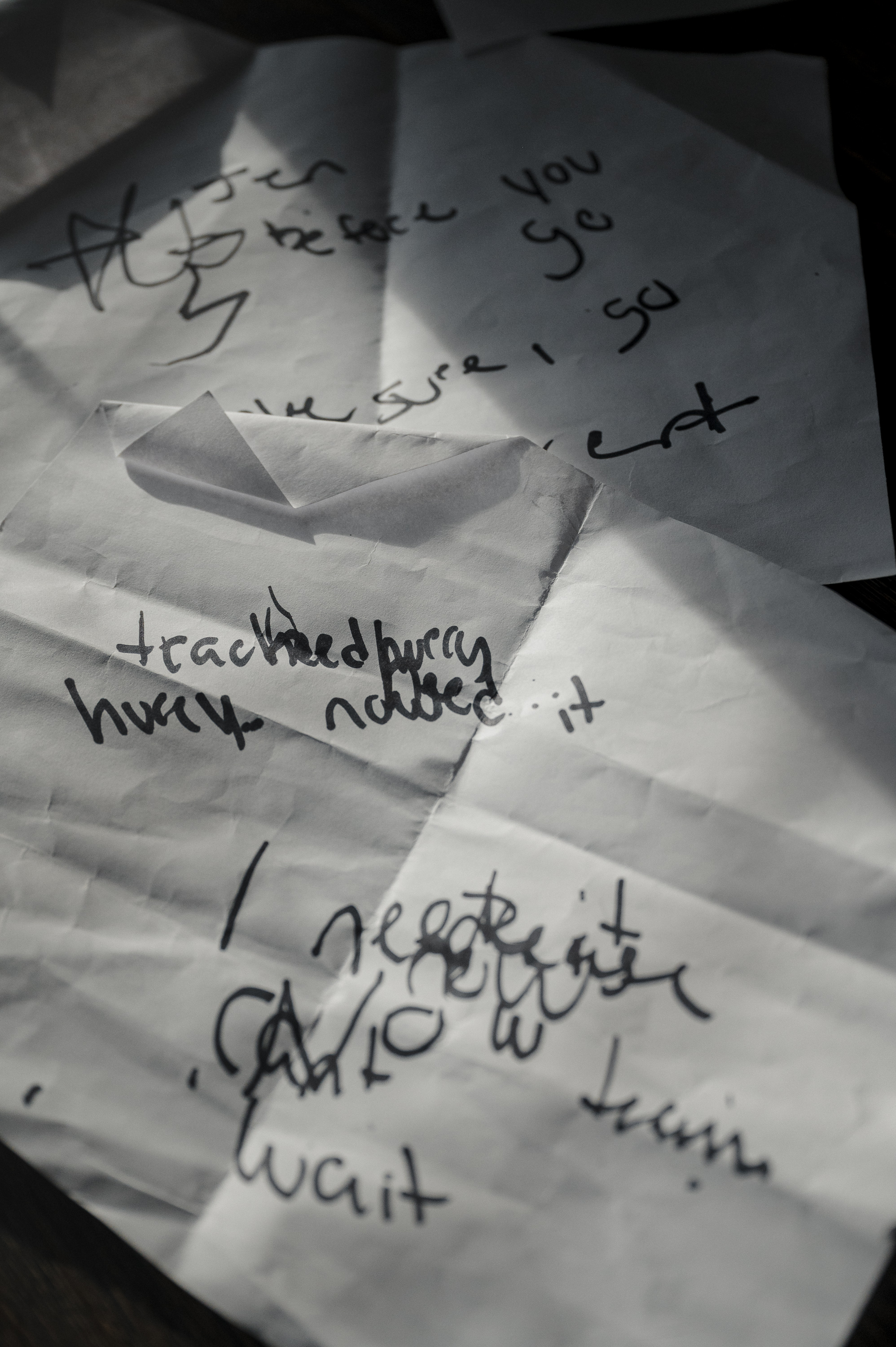

Doctors wanted Hannah to be able to stand up and walk, a sign she was strong enough to survive a second transplant. Holly encouraged Hannah to push through the discomfort, thinking to herself, “You’ve got to show them you want to live.” Hannah lacked the energy to even speak most days. She agreed when the transplant team proposed a tracheostomy, a surgical procedure to place a tube into her windpipe to help her breathe. That way, she could have the benefit of a portable ventilator and still do the required physical therapy. On a sheet of printer paper, she wrote in shaky letters that she needed the vent.

“hurry”

“hurry”

At 3 in the afternoon after Hannah received the tracheostomy, the transplant team called a meeting with Hannah’s family. Standing in a conference room in clothes she’d worn for days, Holly listened in shock as doctors explained that Inova would no longer consider Hannah for a transplant. Hannah was underweight, she had poor kidney function that would likely require dialysis and she had a persistent sinus infection. Hannah was simply too fragile.

How could you deny someone so young? Holly asked again and again. What about the medication, the Dr. Reddy’s? No one had told her to look out for that until Hannah was already in rejection. Didn’t they owe her another chance?

Over the next few days, while Hannah was sedated, Inova searched for other transplant programs. Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia was the only facility willing to evaluate her. She’d have to start over with a new transplant team.

Who’s going to tell Hannah? Holly asked. It wasn’t going to be her.

Hannah lay in the intensive care unit with her blond hair slicked back off her face, puffy from the side effects of aggressive medications. She was gently roused from sedation. Several transplant doctors hovered at her bedside. Hannah looked with confusion at her mom and grasped her hand.

Christopher King, Hannah’s favorite among her transplant doctors, tried to help her understand what was happening. “You’ve been a little bit in the dark for the last day or so. You’ve been sedated,” King said. “Things have changed a little bit over that time.”

He told her he wasn’t sure she’d survive a second transplant. He didn’t want to put her through more suffering if, in the end, it wouldn’t help. “We don’t think we should offer you a transplant here,” he said.

Hannah, unable to speak because of the tracheostomy tube, reached her pale hand for a marker and wrote on a small dry erase board: “I don’t wanna die. I’m only 21.”

King told her she could go to Temple, but she would need to be off the ventilator during the day and be able to walk a lap around the ICU to be eligible for a transplant. Even if she could do that, a transplant was not guaranteed.

“Do you want me to give you some time?” King asked.

Holly watched her daughter fade back into sedation, and she knew: Hannah was done fighting. Holly had begged the surgeon to do everything to keep Hannah alive. She had begged the director of the transplant program. She had begged other hospitals. She would not beg her daughter.

“I’m sorry,” Hannah wrote after waking a short time later. She didn’t want to try for a second transplant. She was ready to let go.

Hannah took her brother’s hand and made him promise he wouldn’t forget her. She FaceTimed with friends, mouthing that she loved them. She pushed to stay awake for goodbyes with her father, grandparents and other family.

As nighttime fell, Holly sat by Hannah’s side, in the glow of two lava lamps. Holly told her how proud she was and that she understood that she couldn’t do it any more. “You’ve made me so happy,” she said. Holly was sorry she hadn’t done something more to save her.

Hannah was gasping for air. She needed more Dilaudid, an opioid that is about five times stronger than morphine.

Holly knew it was time. She walked out into the harsh light of the nurses’ station and requested the drugs that would slip her daughter into unconsciousness for good. “Is this really happening?” she thought to herself. “Did I just talk to her for the last time?”

At 10:48 p.m., the doctors removed Hannah’s ventilator.

Holly found a note in Hannah’s phone: “dear mom, i think eventually you will find this, and when you do i don’t want you to get sad.” She assured her mom she’d had a great life, “and you truly are my best friend.”

“i fought so hard and this time luck just wasn’t on my side.”

When Hannah died at 8:19 in the morning on July 16, 2023, eight years had gone by since the FDA’s first study raised questions about Accord. Two years had passed since the FDA had definitive results that Accord didn’t match the brand-name medication.

Two months after her death, in September 2023, the FDA finally took public action. The agency announced that Accord’s tacrolimus doesn’t “provide the same therapeutic effect” as the original brand-name medication. That step would stop many prescriptions, since some states bar pharmacists from automatically dispensing a generic flagged in that manner. Still, in the very next sentence, the FDA added, the pills remain “FDA-approved and can be prescribed.” The agency told ProPublica that it needed two years to review and release the study results in order to “evaluate the potential public health impact” and determine what to do about the drug. (The FDA answered questions about its handling of tacrolimus generics but didn’t respond to questions about Hannah’s specific case.)

The problem, the agency stated, was that Accord’s drug could provide a toxic dose to a patient. But the FDA said that did not cause an increased risk for organ rejection, because the amount of drug in the body when measured at its lowest concentration was not significantly different than the brand drug.

The FDA should have moved quicker, Janet Woodcock, the longtime head of drug safety for the agency, told ProPublica. “This obviously is a quality problem with Accord,” Woodcock, who retired in 2024, said. Scientists had gotten caught up in debate about how significant the results were, she said. “That doesn’t excuse the fact that the agency should immediately jump on these things and try to sort them out,” she said, adding that tacrolimus for transplant patients is “crucial to health and should be right.”

An Accord spokesperson said in a statement that the company can not comment on individual cases but that it is “dedicated to patient safety, product quality and regulatory compliance.” Accord maintains that its tacrolimus is safe and effective. The FDA recommended in 2023 that the company do new studies to prove its bioequivalence, but shortly after, the FDA banned two of Accord’s factories in India from selling drugs in the United States, citing a “cascade of failure” in the company’s manufacturing. The work on tacrolimus is on hold while the import ban remains in place.

ProPublica hired Valisure, an independent lab, to test both Accord’s and Dr. Reddy’s tacrolimus. Valisure used peer-reviewed methods designed to compare the quality of generics, a method adopted by the Department of Defense. The tests concluded that Accord dissolved too quickly, raising the possibility of too much active ingredient at the outset and then too little after the surge. In tests that focused on dosage, three out of seven sample batches didn’t provide enough of the medication, including pills that were supposed to be 0.5 milligram, 1 milligram and 5 milligram doses.

Dr. Reddy’s tacrolimus, which is still sold in the U.S., also fared poorly. The lab found that it dissolved up to twice as fast as the brand-name drug. A 2021 study by Cleveland Clinic doctors found similar results.

A Dr. Reddy’s spokesperson said in a statement that the company’s version of tacrolimus was approved based on rigorous studies; the statement added that all batches sold in the United States have met FDA specifications and FDA studies didn’t reveal any problems with its tacrolimus. The company said the independent lab did not use the FDA-approved testing method, so the results “cannot be considered an accurate representation of Dr. Reddy’s dissolution performance.” Dr. Reddy’s did not receive a complaint about Hannah’s case nor any other complaints that “indicated any concerns in patient safety,” according to the statement. “Patient safety and consistent product performance remain our highest priorities.”

Hospitals like Inova and the Cleveland Clinic today advise patients not to take Dr. Reddy’s and Accord’s tacrolimus. Cochrane had another lung transplant patient die this year after experiencing rejection that he ties to Dr. Reddy’s tacrolimus. Like Hannah, the patient received that brand despite Inova’s instructions on the prescription, and it’s impossible to say with certainty what caused the organ rejection. Since 2019, Cochrane has reported to the FDA database that tracks “adverse events” related to drugs four episodes in which he suspected that Dr. Reddy’s tacrolimus contributed to organ failure or the death of a patient.

Cochrane understands that patients could use brand-name tacrolimus and still suffer organ rejection. And no one knows what exactly caused it in Hannah’s case.

But Cochrane told ProPublica, “I believe her medicine contributed to her rejection.”

Holly wants to hold someone accountable, but it’s extremely difficult to sue the FDA and lawyers told her it was impossible to draw a straight line from Hannah’s death to a generic manufacturer.

Holly is tortured by the question of whether Hannah would still be alive if she had been on a different brand of tacrolimus: “I just wish I had known.”

These days, with Hannah’s younger brother at college, Holly’s house feels too quiet. Each night, she falls asleep holding Hannah’s worn pink blanket.

#FDAs #Lax #Generic #Drug #Rules #Put #Patients #Lives #Risk #ProPublica