The number of prisoners paroled in Louisiana has plummeted under Gov. Jeff Landry to its lowest point in 20 years, the most visible impact of the “tough on crime” policies he campaigned on.

The parole board freed 185 prisoners during Landry’s tenure compared with 858 in the two years before his January 2024 inauguration, a 78% drop, according to a Verite News and ProPublica analysis of data provided by the Louisiana Board of Pardons and Committee on Parole.

Hundreds of people who would have been paroled under previous administrations now remain in state prisons with little chance of earning an early release through good behavior or by showing they are fit to reenter society and are unlikely to reoffend.

Landry — a former state attorney general and sheriff’s deputy — and his fellow Republicans in the state Legislature overhauled Louisiana’s parole system through a 2024 law that banned parole altogether for anyone convicted after Aug. 1 of that year.

The overhaul also impacted the tens of thousands of people incarcerated before that date who must now meet tightened eligibility requirements to be considered for early release: Prisoners need to maintain a clean disciplinary record for three years instead of just one. And they must be deemed to pose a low risk of reoffending through a computerized scoring system, which does not take into account prisoners’ efforts to rehabilitate themselves and was not intended to be used to make individual parole decisions. Louisiana is the only state using such risk scores to automatically ban people from the parole process, according to a previous investigation by ProPublica and Verite News.

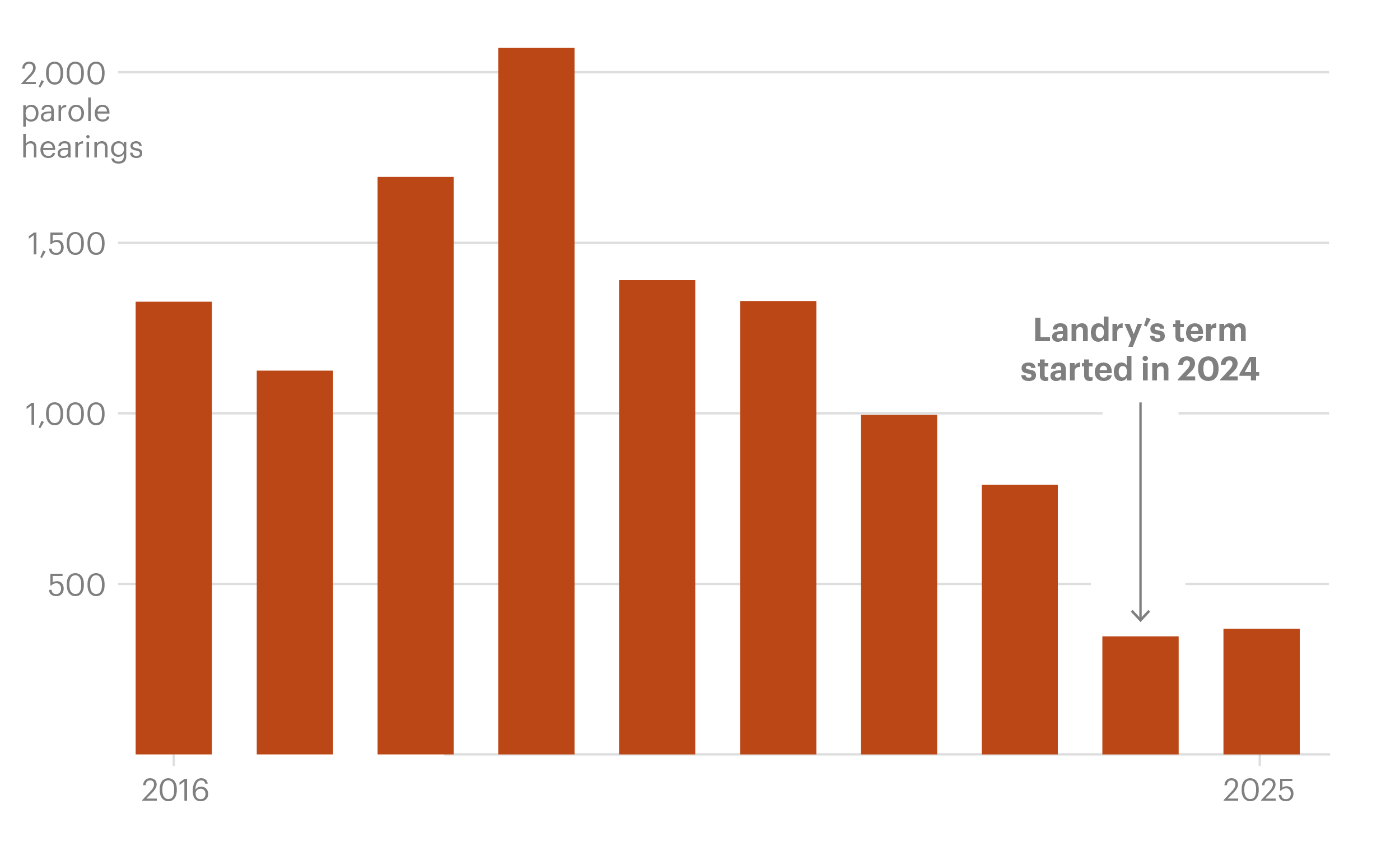

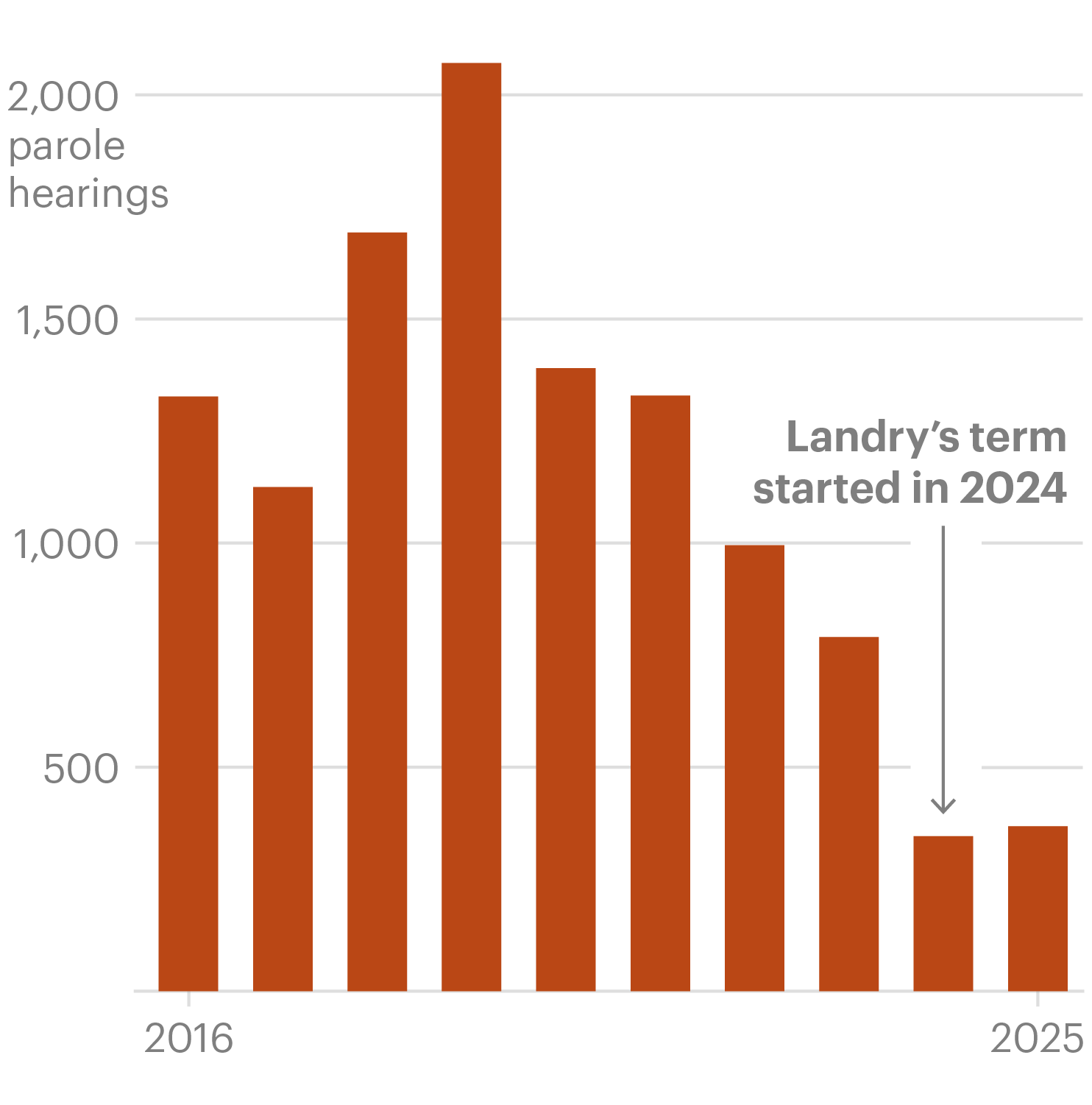

The cumulative impact of these changes has caused the number of parole applications to dramatically fall. In the two years prior to Landry’s inauguration, the board held 1,785 hearings. That number dropped to 714 in Landry’s two years as governor.

The Number of Parole Hearings Dropped to Its Lowest Level in at Least a Decade Under Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry

Lucas Waldron/ProPublica

Landry’s approach represents a fundamental shift away from the original intent of the parole system, said defense attorneys, former inmates and civil rights lawyers. The possibility of parole offers an incentive for prisoners to better themselves while behind bars. And the supervision in place for parolees helps them reintegrate in hopes of preventing them from returning to prison.

“People who have done everything asked of them and would normally be on a fast track to get parole, to get out and make money and take care of their families, they’re crushed and their families are crushed,” said Jim Boren, president of the Louisiana Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “It creates a sense of despair.”

Even those who manage to satisfy all of the new eligibility requirements and make it before the parole board face steeper odds, in part because five of the seven members have now been appointed by Landry.

In weighing their decision, Landry has said, parole board members should prioritize the recommendations from crime victims and law enforcement. But critics say that board members have gone further, focusing almost exclusively on parole applicants’ criminal records, sometimes even disregarding the wishes of victims and law enforcement when they support prisoners’ early release.

In August, Jessie Soileau begged for the release of her son, Ray, before the five-person panel hearing his parole case. He was approaching the final years of his 14-year sentence for punching her in the eye and then fighting the police as they attempted to arrest him, among earlier crimes. She told the board members she needed her son’s help because she’s suffering from a host of health issues and only has one leg.

“I try to do the best I can alone, but I can’t do it by myself,” she said. “Ray is the one that helps me out.”

Ray Soileau told the board he was off his medication on the day of his arrest and promised that he wouldn’t get in trouble anymore.

“I learned my lesson,” he said, “to obey my mother and to obey the laws of the system.”

Caleb Semien, assistant police chief of the Mamou Police Department whose officers arrested Soileau, has known him for 24 years and agreed he should be freed. Semien told the board Soileau has attended church faithfully while incarcerated and vouched for him as “just all around a good guy.”

The testimonies helped sway four of the five board members, including two appointed by Landry, to vote to parole Soileau. But another Landry appointee, Carolyn Stapleton, who worked in victims services in law enforcement for 20 years before retiring, said she considered Soileau a danger to his family and rejected his application despite the endorsement from police and his mother’s pleas.

“I know she needs you,” Stapleton told Soileau, “but she doesn’t need that kind of help.”

That single no vote was enough to block Soileau’s release. And instead of being eligible to reapply for parole again in two years, as had been the case before the new law, Soileau must now wait five years.

Verite News and ProPublica could not reach Jessie Soileau; a family member said she lives in a nursing home but did not know where. Semien did not respond to calls for comment.

Landry, in pushing for a crackdown on parole, said “misguided post-conviction programs” return “un-reformed, un-repentant and violent criminals to our neighborhoods,” causing violent crime to rise and making communities less safe. “Those being released come back into the system again and again,” he said in a speech kicking off a special legislative session on crime weeks after his inauguration.

In fact, people released at the end of their sentences had a five-year recidivism rate that is nearly twice as high as those released on parole — 40.3% versus 22.2%, according to the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections’ 2023 annual report, the latest year for which data is available.

Landry’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

The new law also requires a unanimous vote for anyone seeking release. Previously, prisoners could be paroled by a majority vote depending on the crime for which they were convicted and as long as they met certain rehabilitative benchmarks.

“Lawmakers expanded this requirement to ensure that parole is granted only when there is full agreement that release will not jeopardize public safety,” said Francis M. Abbott, executive director of the Louisiana Board of Pardons and Committee on Parole, in a statement.

Board members are randomly assigned to hear parole cases, typically serving on three-person panels. A five-member panel is required when an inmate has been convicted of a violent crime against a police officer or in some cases involving life sentences. (That was the case with Ray Soileau, whose parole also would have required a unanimous vote prior to the Landry administration because his conviction involved the assault of a law enforcement officer.)

Two of Landry’s five appointees, including Stapleton, have been the least likely of the current board to grant parole, having voted to do so in only about 21% of cases. By contrast, board chair Sheryl Ranatza, who had been appointed by Landry’s Democratic predecessor, John Bel Edwards, voted to release prisoners at nearly twice that rate.

Abbott said the recent decline in the number of parole hearings and approvals can be attributed to a number of factors — not just the legislative changes enacted in 2024.

Edwards pushed through a series of laws passed by a bipartisan Legislature in 2017 that were designed to reduce the state’s prison population — and save money — by expanding the pool of people eligible for release, among other changes. That led to a rise in the number of hearings held and prisoners paroled. Once that pool was depleted, the number of parolees began to drop. As a result, Abbott said, people convicted of violent crimes and sex offenses now make up a higher percentage of the state’s prison population.

“This equates to more complex cases being considered by the Committee on Parole,” Abbott said in a statement. “The reforms of 2024 were designed by the Louisiana Legislature and reflect the will of the citizens of Louisiana.”

Steve Prator, a former police chief and sheriff in northern Louisiana, is the other Landry parole board appointee least likely to grant parole. As Caddo Parish sheriff in 2017, Prator voiced his objections to Edwards’ criminal justice legislation. He said it would result in the release of “good” prisoners whom prisons depended on “to wash cars, to change oil in our cars, to cook in the kitchen, to do all that, where we save money.” Critics, including civil rights attorneys, accused Prator of supporting the exploitation of inmates for his own benefit and said he was therefore unfit to serve on the parole board.

Neither Stapleton nor Prator responded to requests for comment. Abbott previously told Verite News and ProPublica that board policy prohibits current board members from speaking to the media.

Verite News and ProPublica reached out to several defense attorneys who have represented prisoners before the parole board in the past two years and none would speak on the record for fear that anything negative said about the board would hurt their clients. Two who agreed to comment on the condition of anonymity said Landry’s overhaul of the board has forced defense attorneys to change how they make a case for parole.

Prior to Landry’s changes to parole, the defense attorneys said they highlighted their clients’ accomplishments in prison to the board: earning a college degree, attending Bible school, repairing relationships with their children. But “none of that crap matters now,” said one of the defense attorneys in southeast Louisiana, adding that the only factors the board cares about now is the crime detailed in the police report and victim opposition. “What we do now is damage control.”

It is rare for prisoners to appear before the parole board with an attorney, but those who did were more likely to be granted early release prior to Landry’s push to make it harder for prisoners to be freed, according to parole experts. Before Landry, the two attorneys estimated that they secured parole for most of their eligible clients. Since the seating of the new board, they haven’t won parole for any.

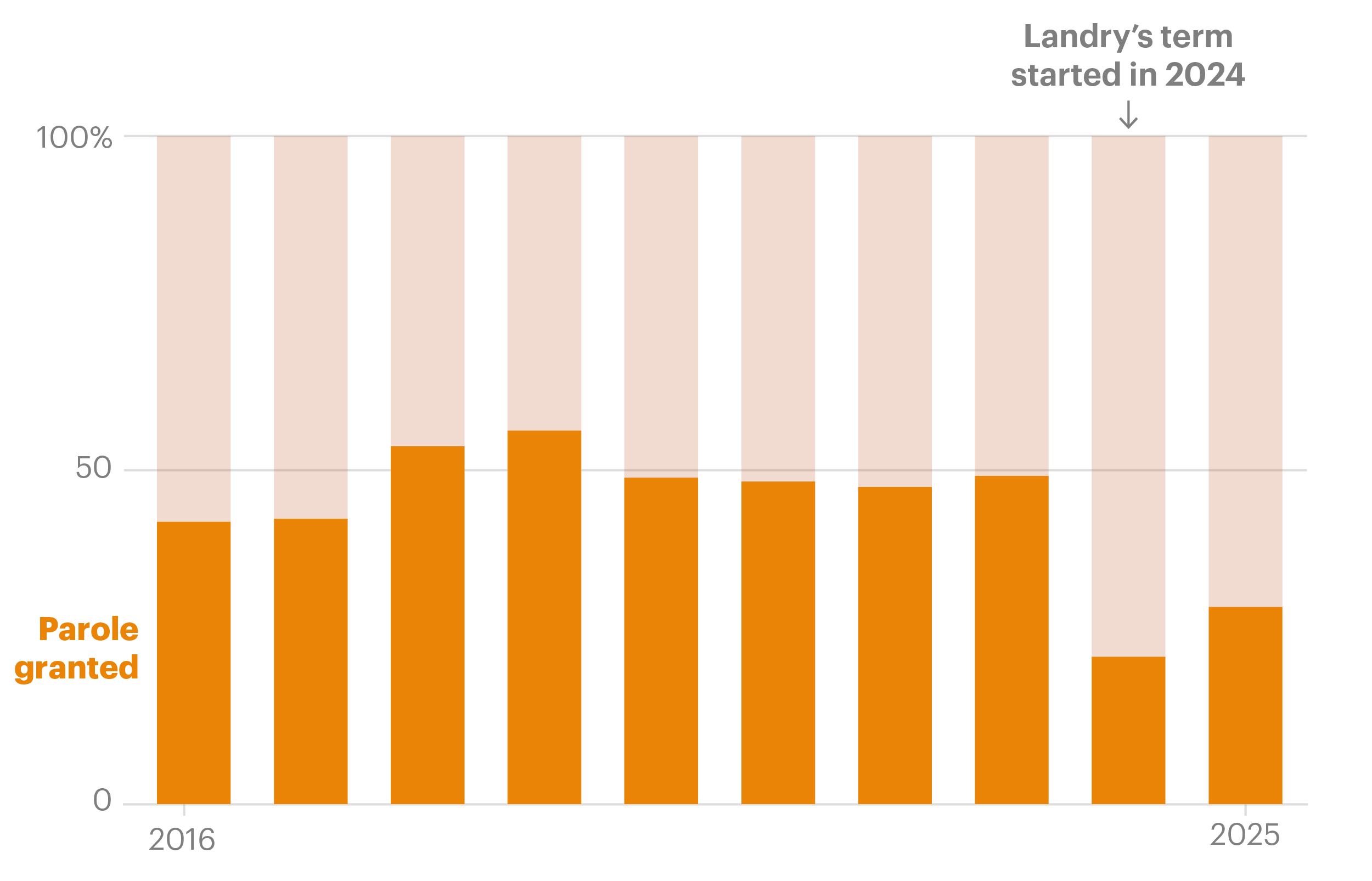

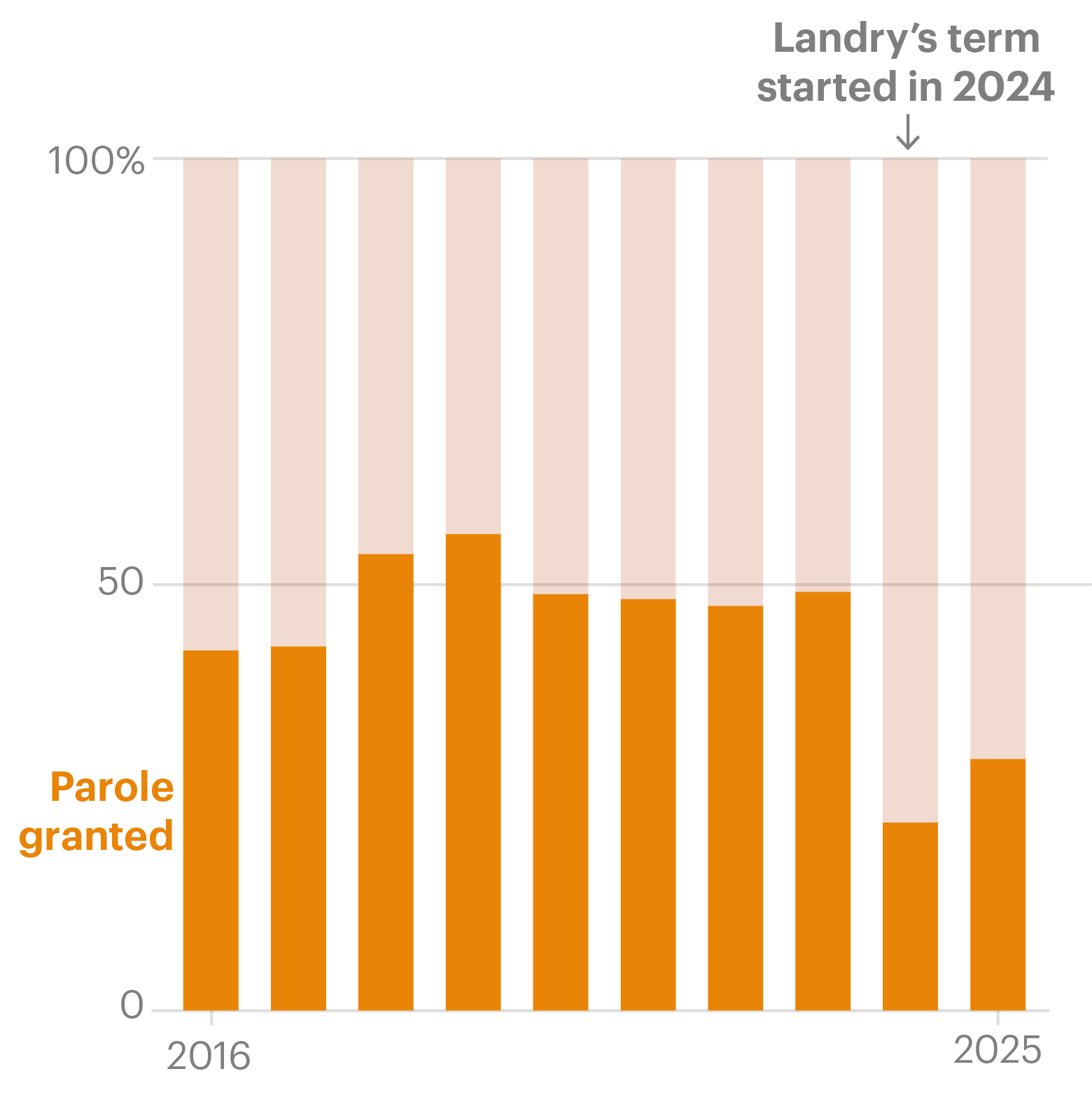

Overall, during Landry’s two years in office, just over a quarter of those eligible have been paroled compared with about half the prisoners who appeared before the parole board prior to his inauguration, according to annual parole rates.

The Rate That Parole Was Granted Decreased During Landry’s Term

Lucas Waldron/ProPublica

Over the past five years, more than two dozen states have been paroling fewer people, a trend attributed, in part, to parole boards being more cautious for fear of public backlash should a parolee commit a violent crime, according to Leah Wang, a senior research analyst with the Prison Policy Initiative and author of an October report on how parole decisions are made.

In addition, some states have passed new laws that put parole eligibility further out of reach, but none have been as aggressive as Louisiana, which eliminated parole entirely for nearly all newly incarcerated prisoners. While 17 states have abolished parole, Louisiana is the first in 24 years to do so.

“No one is doing it well,” Wang said. “But Louisiana is an outlier. It’s a disaster.”

Civil rights attorneys and prison reform advocates say Landry’s changes represent a return to the failed policies of the past, which they said resulted in violent, overcrowded prisons and did not make a dent in the state’s high crime rates.

“Tough on crime doesn’t work,” said Pearl Wise, who was appointed to the parole board by Edwards and served from 2016 until 2023. “All it produces is mass incarceration, which costs us more than rehabilitating the individual and making them taxpayers, not tax burdens.”

James Austin, a national corrections policy expert, estimates that the state’s prison population will nearly double in six years — from about 28,000 to about 55,800 — because of recent policy changes. Since Landry took office, the prison population has increased by about 1,700 inmates, but there is not enough data to show whether this is a permanent trend. It costs about $37,000 per year to house a single inmate in a state prison compared with about $2,200 a year for parole supervision.

One of those prisoners who will remain incarcerated because of Landry’s policies is Tyrone Charles, who was 20 years old when he was arrested for armed robbery and sentenced in 1995 to 50 years in prison as a repeat offender.

When Charles appeared before the parole board in July at the age of 53, he told the three-member panel that he had learned the value of his own life — and that of others — during his three decades in prison.

“I would like to apologize to my victim today, to their family,” Charles said. “I apologize to the police. I apologize to my family, to all the people that I hurt, for the pain and suffering that I caused as a young man. Now, I’m older, I know the meaning of love, to just be a loving person.”

Terrance Winn, who runs a Shreveport-based nonprofit offering services to people released from prison, befriended Charles while they were both serving time in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. He told the board he would provide Charles with whatever was necessary, including housing and employment, to ensure his post-prison life was a success.

Prator, whose detectives investigated the robbery when he was Shreveport police chief, cast the lone no vote.

Winn, in a recent interview, said he was not surprised by Prator’s denial. In the three years prior to Landry’s inauguration, 17 of the 18 people Winn advocated for during that time were granted parole. Since Landry became governor, Winn said the outcome has flipped, with 10 denied and only two approved.

“With this new parole board,” he said, “you got to expect the worst.”

#Louisiana #Paroles #Lowest #Number #Prisoners #Years #ProPublica