Reporting Highlights

- Disparate Punishment: A ProPublica review of Alabama incarceration data showed that some immigrants received unusually long sentences, even when they had fewer prior offenses than citizens.

- Constitutional Protection: The Supreme Court has ruled that noncitizens accused of crimes are entitled to the same rights as citizens. That extends to equal rights in sentencing.

- National Efforts: State and federal lawmakers have pushed for laws that would give undocumented immigrants longer sentences for crimes, raising constitutional concerns.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

Time and again in Alabama, immigrants face harsher punishments for the same crimes as citizens, even when they have fewer prior convictions, a ProPublica review of more than 100 court cases found.

The cases include a Mexican immigrant who caused a fatal car crash and received a 61-year sentence — which exceeds the sentences of about 93% of all inmates convicted of similar crimes. Sent to prison in 2000, he’s one of the noncitizens who’s been incarcerated in Alabama the longest.

An immigrant detainee who set fire to his mattress inside a jail cell received a sentence twice as long as a citizen with a similar criminal history who committed the same offense in the same facility three months later.

And in a case ProPublica recently covered, a Mexican immigrant who crashed into a car and killed the driver received a sentence four times longer than anyone else involved in fatal crashes in that circuit court.

We identified these cases using data provided by the Alabama Department of Corrections covering the 156 currently incarcerated people who self-identified as noncitizens. They represent a tiny slice of the overall inmate population, less than 1%.

The U.S. Supreme Court has consistently ruled that noncitizens accused of crimes are entitled to the same rights as citizens. That extends to sentencing, which should not be influenced by the nationality or immigration status of the defendant. In the cases identified by ProPublica, defendants said they believe their citizenship status tipped the scales of justice against them.

The small number of inmates on the list and the complicated nature of criminal sentencing make it difficult to draw broad conclusions. Sentences can be longer if the defendant has a criminal history, targeted a young child or used a gun.

But academic research has found that incarcerated immigrants face tougher punishment on average, with sentences that are longer by months or years than nonimmigrants. Michael Light, a sociology professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, looked at the role of citizenship in both federal and state courts in California and Texas, which, unlike Alabama, keep detailed information about defendants’ citizenship status.

He found the starkest differences in Texas, where noncitizens received sentences 62% longer than citizens, even with the same charges and criminal backgrounds. The disparities exceed those between white and nonwhite citizens. Another researcher, University of California, Los Angeles law professor Ingrid Eagly, found similar results in her study of Harris County cases in Houston.

Several factors can increase sentences for immigrants convicted of crimes. In some cases, Eagly said, the differences could come down to the judge.

“Judges could be punishing them for their immigration status in addition to punishing them for the criminal conduct,” she said. “Of course, punishing someone for their immigration status isn’t what we do in criminal courts, right? It’s something that the immigration system is supposed to handle.”

In October, ProPublica published a story detailing what lawyers consider one of the most egregious cases of excessive sentencing of an immigrant in Alabama: the 99-year prison sentence handed to Jorge Ruiz for a fatal car crash. Ruiz was not charged with DUI or even reckless speeding. He had a clean criminal history. Yet his 2018 sentence was almost four times longer than those handed down for similar crimes in the same circuit court over the past two decades.

Last year, a court reduced that sentence to 50 years, which is still twice as long as any other crime involving a fatal car crash in the county. His appeal of the sentence is pending. The prosecutor in Ruiz’s case said he did not treat the defendant differently because of his race or citizenship status and that the long sentence was warranted because Ruiz was a minor driving with alcohol in his system. Neither the judge who handed down the 99-year sentence nor the one who handed down the 50-year one responded to requests for comment.

In the course of examining Ruiz’s case, we looked for examples of other immigrants in Alabama’s criminal justice system to see whether they too were serving a more severe sentence than citizens who commit similar crimes. One happens to be a friend he’d made at Ventress Correctional Facility.

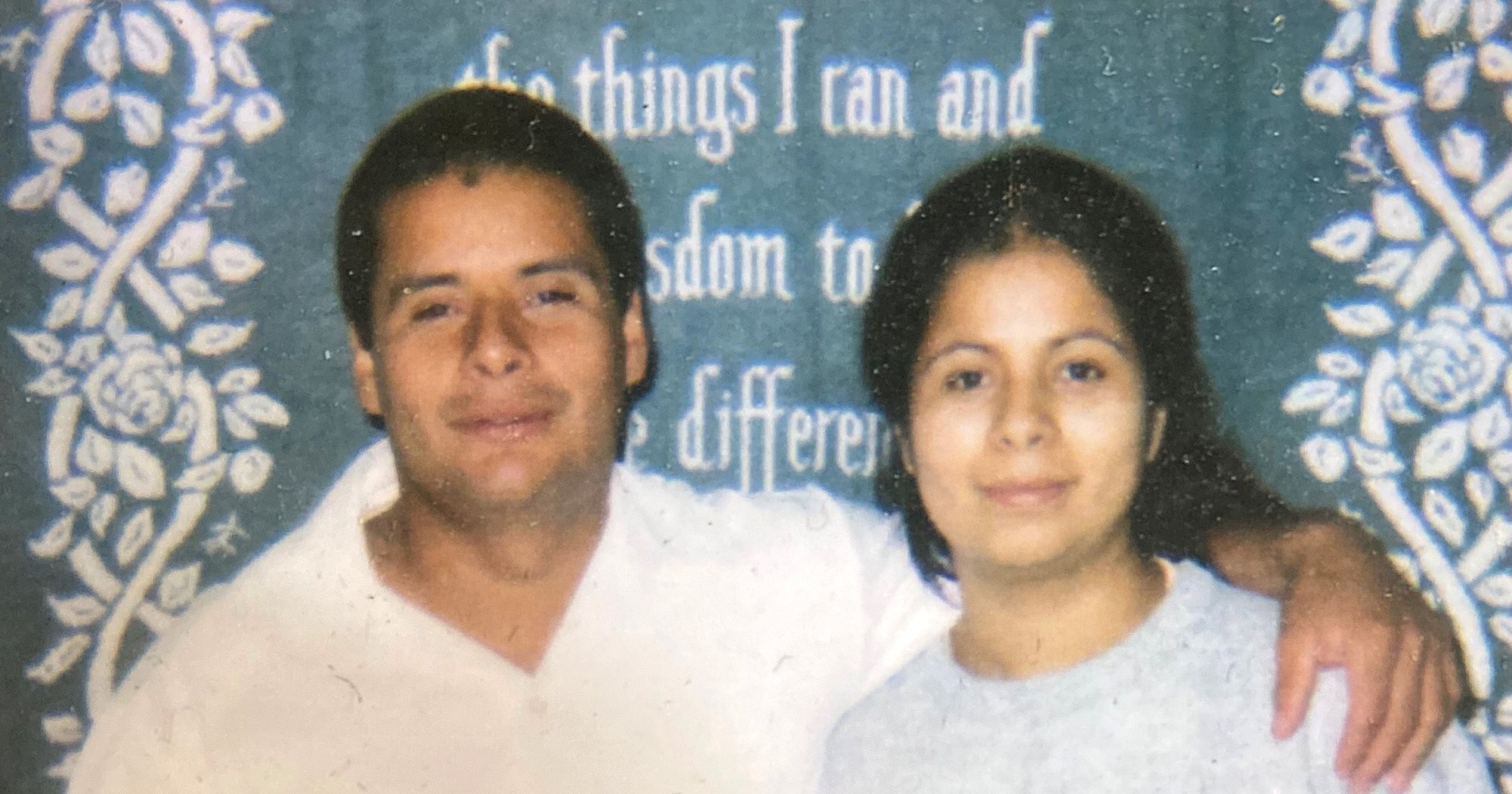

Heriberto Arevalo Robles is 25 years into his 61-year sentence. That’s the longest sentence for any Alabama inmate currently incarcerated for assault, manslaughter or both who has no prior felony convictions.

Robles has spent more than half his life locked up for a July 1999 fatal car crash near the small town of Heflin in east Alabama. It was raining hard that night and Robles had been drinking. He crashed head on into a van carrying six people, killing the driver.

A blood test found alcohol in his system at a level that exceeded the legal limit. Initially, the criminal justice system seemed forgiving. Although he couldn’t pay his bond, the sheriff at the time allowed him to work nights to support his family. He even let Robles come home for a long weekend on Easter. His wife, Johnnie Arevalo, took it as a sign that she would soon be reunited with her husband.

As the trial approached, her hopes dimmed. In a bond reduction hearing, a police officer testified that he had heard Robles say that “as quick as he gets a chance, he’s going back to Mexico,” according to the transcript. (Robles’ attorney disputed at a bond hearing that his client said that.) The sheriff stopped letting him out to work.

Almost a year after the crash, a jury found Robles guilty of manslaughter for the death of the driver, as well as five counts of assault for each of the five passengers. Some of them sustained serious injuries, including one woman who suffered so much damage to her face that she later told authorities that she couldn’t look in the mirror for a year.

The family and the prosecutor asked the judge to run the sentences for each charge back-to-back for a total of 82 years behind bars. The prosecutor, who’s now the judicial circuit’s district attorney, did not respond to requests for comment.

Courts rarely punish defendants in car crash cases with prison sentences that are stacked that way. ProPublica found only one other case in a review of the dozens of inmates incarcerated for manslaughter and assault. The judge in Robles’ case decided to give him stacked, back-to-back sentences: 20 years for manslaughter and an additional 41 years for the five assaults.

Robles said in an interview from prison that he believes his status as an immigrant, even though he was a lawful permanent resident, affected his sentence.

When asked whether Robles’ status played a role in his long sentence, Judge Malcolm Street, who’d presided over the case, said no. But Street, who is now retired, also said he couldn’t immediately recall all the details of the case or why he gave such a long sentence.

In 2000, Robles missed a key deadline to appeal his case. In a federal court filing, he blamed his lack of English proficiency and unfamiliarity with the court system. Instead, he has sought relief from the court where he was convicted.

In a recent filing, his attorney argued that the court erred by ordering the sentences to run back-to-back because it punished Robles several times for a single reckless act. If he had crashed into a car with one driver, he would be out of prison by now.

“He has already been in prison for over 25 years, five years more than the entirety of his manslaughter sentence,” according to his brief. “There is no benefit to the State, no benefit to the victims, and no public interest served by keeping Robles incarcerated for his one act of impaired driving.”

Inmates light fires in jail frequently and for a host of reasons: to mask the smell of smoking, to draw attention to their grievances or in the midst of mental health crises. One organization estimated that 600 fires break out in prisons every year.

Many fires get extinguished quickly and go unreported. Others can lead to chaos and tragedy. In 2017, a series of fires set at the Etowah County Detention Center in east Alabama illustrate the differences in punishment for nearly identical crimes.

In May 2017, a group of Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees held at the jail through an agreement with the federal government started a fire to draw attention to the facility’s conditions, which advocates had described as inhumane. (An Etowah County Sheriff’s Office spokesperson said the current sheriff has worked to fix the problems: “Substantial improvements have been made in the safety, security and overall conditions,” he said.)

Nigerian-born Okiemute Omatie had been in the facility for more than five months. He and three other men used a wire brush and an electrical outlet to ignite a piece of paper. Omatie then placed it on his mattress, which caught fire. His cell filled with smoke and officers evacuated several detainees. It created a potentially dangerous scene, law enforcement would later say, but no one was injured.

Omatie pleaded guilty to arson in February 2018. Etowah County Circuit Court Judge David Kimberley sentenced him to 20 years in state prison, which is what the prosecutor recommended.

“I got 20 years for a burned mattress,” Omatie said.

Over the next six months, other inmates who were not immigrant detainees started fires inside the Etowah County Detention Center. In August 2017, two inmates used an electronic cigarette to ignite debris on a food tray. Then, a few weeks later, another inmate sparked a fire inside the jail. Officers quickly extinguished both blazes.

The three men pleaded guilty and each received the prosecutor’s recommended sentence of 10 years in prison for arson.

Prosecutors pointed out that Omatie had a prior felony, second-degree assault. But so did one of the detainees who received a 10-year sentence. He’d been convicted of burglary, theft, breaking and entering into a vehicle and fraudulent use of a credit card. He’d received a longer sentence for those crimes than Omatie did for his prior felony.

The green card holder had received an 11-month sentence for second-degree assault in New Hampshire, where he’d lived with his mother. He was later arrested for robbery, but the charge was dropped because officials had initiated deportation proceedings.

Omatie described being distraught due to the separation from his mother and his young son and said he made a “bad decision” regarding the fire. He also said he felt he should be deported rather than tried for the arson.

The prosecutor, when asking for the 20-year sentence, said Omatie should not be allowed to return to Nigeria. Neither the Etowah County district attorney’s office nor the judge who oversaw the case responded to requests for comment.

“If he doesn’t go to prison, he will be getting just what he wanted,” said Etowah County Chief Deputy District Attorney Marcus Reid. “His whole ploy, his whole scheme to start a fire to endanger everybody in the jail will have worked.”

Omatie told ProPublica he believed he was punished more harshly because he was an immigrant.

“I think it was racism and because of where I’m from,” he said.

Immigrant crime has become a potent political issue in recent years, and states have rushed to consider bills that would punish them more harshly than citizens. Although an Alabama bill that would have automatically increased the severity of some felonies and misdemeanors committed by undocumented immigrants died in 2025, other measures succeeded. A bill in Florida adding additional punishments for undocumented immigrants passed, but it has been challenged and is on hold.

Judges and district attorneys in Alabama are elected, and both play key roles in sentencing. Most defendants take plea deals offered by prosecutors, who recommend a sentence length to the judge. Judges ultimately determine the sentences both for those who plead guilty and those who go to trial.

“Judges tend to sentence noncitizens to longer sentences than U.S. citizens,” said Juliet Stumpf, a professor at Lewis and Clark Law School who studies the intersection of immigration and criminal justice. “And there’s some theories about why that’s true, but some of them have to do with maybe the judges or prosecutors who are asking for these longer sentences are seeing these particular noncitizens as more dangerous or more undesirable.”

But well before a judge hands down a sentence, bias can factor into a case in a way that leads to longer sentences.

“The truth is, we’re almost all saddled with all the packaging we came with,” Madison County District Attorney Robert Broussard said. “If the defendant is from another country in front of 12 U.S. citizens, we’d be kidding each other if we said justice is blind.”

If the defendant is from another country in front of 12 U.S. citizens, we’d be kidding each other if we said justice is blind.

Robert Broussard, Madison County district attorney

Broussard said his office doesn’t treat people differently because of their race or citizenship. But he conceded some juries might be less forgiving in cases involving immigrant defendants.

We had reached out to Broussard about a 2015 case he’d prosecuted against a Nigerian immigrant charged with attempted murder of a police officer. Olusola Kuponiyi got a 40-year sentence, which is only slightly higher than the average sentence for that crime. But Kuponiyi’s case stood out in that most people who face that charge fired a gun at an officer, while Kuponiyi got into a fight with an officer who drew his own knife, and each man stabbed the other.

Broussard said that since Kuponiyi tried repeatedly to pull the officer’s gun out of its holster, it needed to be elevated to attempted murder.

But some citizens also charged with attempted murder received much shorter sentences than Kuponiyi’s. A man who shot an off-duty state trooper and a 6-year-old received 21 years in prison. Another was sentenced to five years for shooting an officer in the shoulder. And a woman who fired a high-powered rifle at agents serving a search warrant got a 30-year sentence.

When asked about those shorter sentences, Broussard said that comparing any of them to Kuponiyi’s is problematic. “It is impossible to compare discrepancies in sentencing of cases under the same charge when considering the variables in arriving at any particular sentence,” he said. “Each case has its own unique set of facts, its own unique inherent strength or weakness in proving the case, its own unique cast of characters, i.e., defendants, lawyers, judges and juries, and its own jurisdictional philosophy on severity in sentencing.”

Northern Alabama defense attorney Ivannoel G. Dollar points out that judges sometimes show more mercy to defendants who can bring character witnesses to speak on their behalf. He said such witnesses can be difficult to source for people in the country without documentation.

“It can be hard to get them to come to court because they may not have documentation,” he said.

Federal sentencing policy shifted after President Donald Trump took office in January. A key change excluded some noncitizens from the First Step program that reduced sentences.

A bill in Congress would take that further, adding extra prison time to all undocumented immigrants convicted of felonies in state and federal court. If it passes, Stumpf said, it could lead to many more instances of the type of disparities that have been playing out in Alabama and beyond. She said the law essentially would create a blueprint by which the court system could mete out vastly different punishments for two defendants identical in every way except their citizenship status — even those who committed the same crime together.

“That would be a serious departure from the principles of our nation’s criminal law system,” Stumpf said, “which focus on a person’s actions, not their status, when imposing punishment.”

#Immigrants #Alabama #Receive #Harsher #Sentences #Citizens #ProPublica